The lab-grown diamond market is in turmoil, facing significant challenges despite its rapid rise in popularity. With plummeting prices and shrinking margins, many producers and traders are struggling to stay afloat. Yet, amidst the financial strain, a path forward remains, offering hope for those willing to adapt and innovate, writes diamond industry analyst Edahn Golan.

Something bad is happening to the lab-grown diamond market, and it shows no signs of changing for the better any time soon.

A superficial look will portray a fantastic story: A new product taking the US jewellery market by storm, unit sales rise weekly, a growing adoption rate, a common discussion topic, and above all – a growing preference for the most coveted jewellery item, diamond engagement rings.

But scratch the surface, and a very different picture emerges. Price declines are a daily occurrence, oversupply is a long-standing issue, producers and traders’ margins are eroding to the point that many are no longer profitable. In fact, there are those who already fear major financial losses.

On the production side, some bankruptcies already happened and a few more are displaying worrying signs regarding their financial viability. They indicate that the standalone grower business model is likely not sustainable.

Traders, who made triple digit margins just a few years ago, are currently down to low double digits or less, leading a sizable number of them to leave LG trading because they don’t see a future in it.

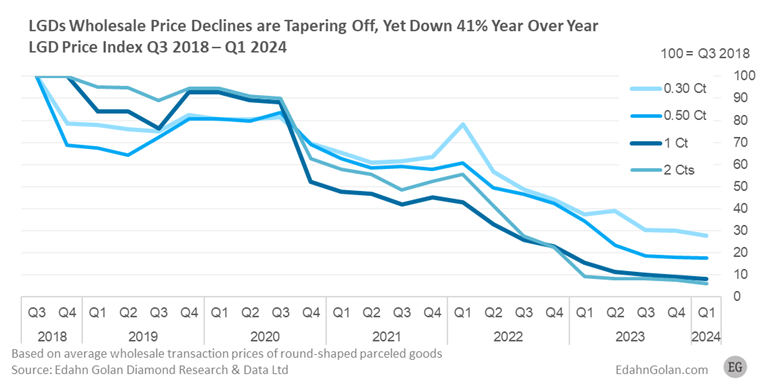

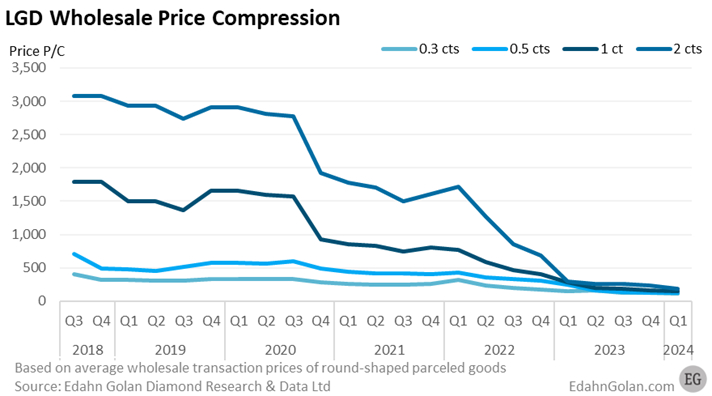

All along, wholesale prices are sinking fast. Wholesale prices of one carat rounds are down more than 40% year over year and two carats are down 45%.

That leaves us with retail activity. There, margins are enormous, 67% for loose and 49% for finished jewellery. However, prices are falling too, and gross profits are impacted.

In terms of real earnings, a triple-digit year-over-year gross profit increase in the first five months of 2021 shrank to just 11% in the January to May period of 2024.

At this rate, where will gross profits be this time next year? I’ll be cautious: they will experience a year-over-year decline, likely falling 5-10% below this year’s gross profits. A basic trend analysis puts it at a much deeper decline.

It’s Not A Surprise

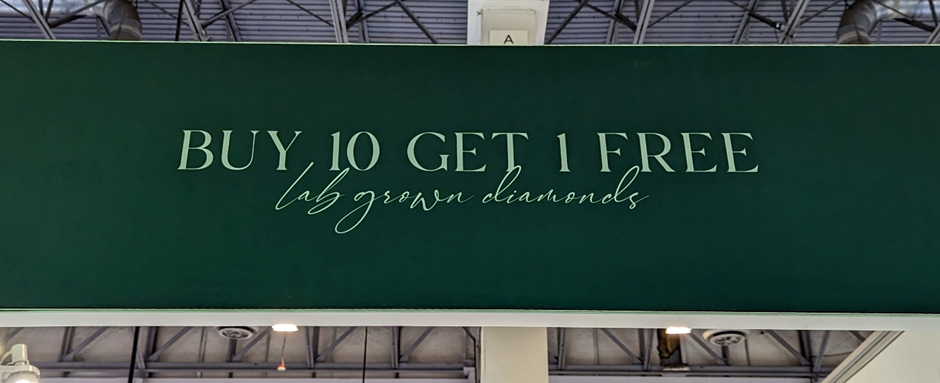

The LGD market got here for a reason. When LGDs were first offered, they were priced a little below natural diamonds, creating an immense gap from costs. Additionally, they were offered as a low-cost alternative, and they still are. We all saw the offer at JCK for $99 per carat. That is just one of many examples. Look at the two images from the show and an online jewellery retailer. Both shout out, “we are cheap.”

JCK Booth Sign

Jewellery Retailer Homepage

These policies result in price declines. The LGD market shot itself in the foot. Add to that some manic tantrum rants from certain quarters of the LGD market that natural diamonds kill children, and you are fully setup for deep and ongoing depreciation.

Not All is Lost

I am not against LGDs. In fact, I find the sector fascinating. I share data that reflects what is happening in the market, not to put it down but because that is the reality of the market.

The downward price trajectory means that LGD is about to see a series of market consolidations. The remaining stand-alone growers will have to partner with manufacturers and getting equity will be involved. If not, they’ll need to find financing until they reach their holy grail – tech applications.

Some US retailers will reduce their LGD offerings to the bare minimum, which means that goods will only be held on memo. They are already advising their customers that LGD, unlike natural diamonds, are not accepted back for trade-ins.

LGD price consolidation is in full swing. If the difference in price is just $10-30 per carat, then we are near the point of a flat $80-90 per carat for an E/VVS lab grown.

At that point, LGD can go in three directions. One is as a low-cost component in moderately priced, well-made branded jewellery, aka the Pandora model. This offers handsome margins to the jewellery company. The second is very low-cost jewellery. Call it the Walmart model, where margins are small and fairly fixed.

The third model is moderate to high-priced branded jewellery, very well made, and takes full advantage of the diamond front and centre. This could take advantage of the low cost of rough LGD and do something very surprising with it. Not luxury like Tiffany, but still doing very well. The downside: a scarce few will achieve it after a massive investment in design and marketing.

If you don’t like this scenario, keep in mind that there is only one way around it: Without digging very deep into their pockets to promote the category in an impactful way, LGD has a very steep uphill battle.

This is a suitable time to remember Barney Barnato. He was a London street performer with a comic magician and musical act in the late 19th century. The news of finding diamonds in South Africa intrigued him, and he decided to take the act to Kimberley, South Africa, where the weather was not as miserable and the performer competition light.

But when the 18-year-old arrived at the mining site, he was shocked by what he found. The place was crowded, many suffered from dysentery due to the poor conditions, and most people were exhausted after long days of hard digging under the harsh summer sun and heavy winter rains.

The business that seemed promising from afar was a lot less appealing up close. Just like LGD today. He decided to start trading rough diamonds but quickly discovered that anyone that found a diamond sold it quickly to generate enough money to survive another day. Diggers’ rush to sell fast resulted in constantly lower prices, a forerunner replayed today in lab-grown diamonds.

Our friend Barney decided to buy up digging claims (consolidation!), sell only in large quantities and at controlled prices. His vision was to sell slowly and efficiently.

It didn’t take long before others came to the same conclusion and did the same, creating competition between them. At some point they overcame their differences and formed a company that took control of it all. They called it De Beers Consolidated Mines. They all lived happily ever after.

Just some food for thought.

Edahn Golan is a diamond industry analyst and commentator, researching and writing about it since 2001. He analyses the full span of this unique industry, from mining to consumer demand. He specialises in taking his primary research data and placing it in its broader context.

Edahn has examined these subjects and many others, including the Kimberley Process (KP), financing issues, the forces that impact diamond price, and the way the diamond industry has evolved over the years.

In addition to his analysis and market research work, Edahn is managing partner at Tenoris (www.tenoris.bi). Tenoris is the only trend data company that tracks US jewellery sales on a per transaction basis. Tenoris is the leading data supplier to the diamond & jewellery industry as well as the financial community.

Over the years, Edahn has advised leading diamond firms, industry bodies, investment companies and governmental agencies, and he is frequently quoted in the world’s leading newspapers.

You can read Edahn’s research and analysis papers on EdahnGolan.com, Tenoris.bi, and welcome to follow him on LinkedIn and X @edahn.