The crash of 2008 was far more benevolent than the coming diamond crash of 2012,” remarked a large Diamond Trading Company (DTC) sightholder, explaining the difference as follows: “In late 2008 and early 2009, the business came to a virtual standstill. We didn’t buy, nor did we sell. Accounts receivables came in. Our banking debt went down. In early 2009, when the business gradually normalised, our activity resumed, prices stabilised – and we emerged from the crisis without major damage. There were hardly any bankruptcies.”

Continues the sightholder: “Today, it is different. There is activity, we buy DTC sightboxes and, month after month, we lose between 10% and 20% on the polished we sell. We are destroying value; we are creating a ‘hole’ that is growing month after month. The ‘smart’ DTC sightholders last week deferred their purchases – which is a code name for ‘leaving goods on the table’.” De Beers’ management reportedly takes mistaken pride in “defending its prices,” however defending unsustainable prices that cause lasting damage to clients, the market and to De Beers itself is a fallacy, a delusion, that will backfire.

By our estimates, some 20-25% of the last sight was not taken. De Beers sold $100 -$125 million less than it had budgeted. And those sightholders who didn’t take their full allocations are the smart ones. As one DTC broker intimated: “DTC prices are still some 7%-10% too high and they must come down. So those who didn’t take the goods now will pay less for them at the following sights.”

Failure of DTC price management

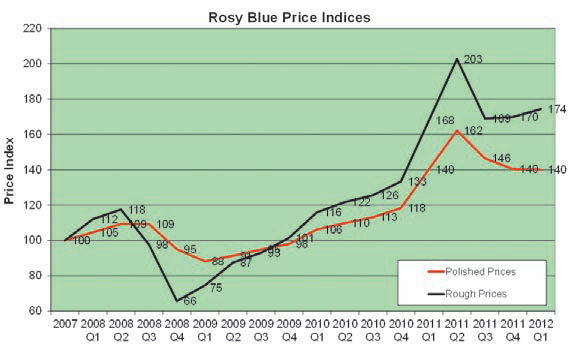

One must differentiate between two separate issues: the extreme price volatility of rough and the widening gap between the rough prices and those of the resultant polished. If one takes the end of 2007 as an arbitrary point of basic price equilibrium, which was before the world’s financial markets imploded, we see that the industry came through the crisis well intact, and by the third quarter of 2009, the rough and polished price movements again were in equilibrium – albeit both at a lower price level. Whoever bought rough at that time would be able to sell the resultant polished at break-even or profitable prices.

Throughout 2010, admittedly a profitable year for the diamond industry, both rough and polished prices rose more or less in tandem; there was a manageable gap in the pace of growth between rough and polished. Keeping rough somewhat “expensive” is ultimately a time-proven way to push polished upwards. There is also a natural time gap, where price increases work their way through the pipeline, and, throughout 2010 and 2011, many traders were willing to speculate and buy rough at (too) high prices, “assuming” that polished would have increased by the time their resultant output reached the markets. They miscalculated in a big way.

Thus in 2011, the market went into a steep upward spiral price-wise: by the third quarter of 2011, rough prices had doubled since the third quarter of 2009, when rough and polished prices had been in equilibrium. Polished price growth, however, then lagged some 25% behind the corresponding rough. That is unsustainable. Then came the third quarter 2011 crash, and most diamond companies literally saw the profits made earlier wiped out. Though producers still made record profits, many of their clients lost money and were left with stocks that had lost, and still were losing, enormous value.

Looking at the demand and supply fundamentals, it became clear that rough prices needed a downward correction to close the gap with the polished prices. At the end of 2011, Mumbai/Dubai’s Pharos Beam Consulting and Tacy Ltd. predicted that rough prices needed to fall – and they did. [This was also stated by us at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) convention in Toronto in early March 2012 as widely reported by Reuters, Forbes and elsewhere.] It was clear that De Beers had dropped its time-honoured policy of “maintaining sustainable prices,” and it was now using – or abusing – its market power as the largest and dominant producer to “overshoot” price-wise. That’s where we still are today.

The new De Beers management, after Philippe Mellier assumed the helm in mid-2011, seems to pursue a short-sighted policy of driving up rough prices while totally disregarding the polished markets. It also seems to have little consideration for the company’s customers who distribute or manufacture De Beers’ output, and who should have an inherent right not to lose money. De Beers doesn’t have ill intentions; the miner simply lacks good market feedback. Mellier may not have realised that clients fear telling him straightforward “how bad things are” – especially in a period preceding client selection. De Beers overestimated the demand side; it assumed supply shortages that were more imaginary than real. That is still the case today.

If rough and polished prices had been in equilibrium by the third quarter of 2009, two years later, that gap had widened by more than 25%.

DTC sightholders don’t need sophisticated economic models to know what went wrong – they see that they are losing vast amounts when manufacturing their DTC sight boxes. At the June 2012 sight, the sightholders rebelled. We are not sure whether this is recognised as such in London – at both De Beers and at Anglo American.

The June 2012 DTC sightholder rebellion

At the end of the most recent sight, DTC brokers and representatives, realising how many goods were “left on the table,” were quick to remind clients that under the terms of the present DTC sightholder contract, not taking one’s ITO (Intention to Offer – the pro-forma supply commitment by the DTC) will “potentially lead to the reduction in the starting point of future ITO’s when contractual allocations are not fully taken up during this ITO period.” [Quote from a broker’s June internet sight newsletter.]

Indeed, many DTC clients face a dilemma: Will I do what is good for my business and refuse to buy rough that guarantees financial losses on the sale of the resultant polished, or do I honour my commitment to the DTC to purchase whatever is offered to me at whatever price it is offered? There is no unequivocal answer, though I told one friend facing this dilemma that he should stop being a sucker and ensure the financial solvency of his business; by simply transferring money to the DTC month after month at losing prices, he will not be around anyway when the next ITO is formulated. So why worry about the level?

On a different level, it seems to reason that De Beers is bluffing. It cannot afford to reduce ITOs next time around. It cannot be sure that others will indeed be willing to take these goods. Nor can it sustain the current absurdity where DTC sight boxes are auctioned by Diamdel at 7-10% BELOW the DTC sight selling prices. Some small lots have gone at even far greater discounts to DTC box prices. This is as absurd as it is ethically and morally questionable. Sightholders who have made a long-term purchase commitment to the DTC end up paying substantially more for DTC goods than those occasional and non-committed buyers participating in Diamdel auctions.

Diamdel destroying the De Beers brand equity value

For Diamdel to destroy financial and DTC brand-equity value by even considering undercutting DTC sightholders is more a manifestation of De Beers’ management’s despair to sell goods than anything else. If, hypothetically, De Beers is budgeted to sell, let’s say, $7 billion-worth of rough in 2012, of which $5 billion would go through the ITO system, and if, theoretically, clients leave $1 billion of ITO goods on the table, the ITO format would say “new ITO’s will be at a level of $4 billion, rather than $5 billion.”

Irrespective of the way the ITO system works, in the present so-called new “dynamic pricing” system, most sightholders will not be willing to get “rewarded” with higher ITOs. I also don’t think that Diamdel clients would want to become sightholders, as at auctions they pick up boxes at BELOW the cost price of the boxes and they are spared the prospects of having to sell DTC sight allocations at discounts. By lowering the ITOs the next time around, De Beers will be creating another obstacle for itself on how to move the goods onto the market. Actually, ITOs have become MORE important to De Beers than to clients.

Message manipulations

De Beers is managing the market (or, we should say, its own market) through certain manipulations including controlling its “messages” (such as saying it is “leaving goods in the ground”). Indeed, the internet sight letter remarks that “for the second consecutive sight in the new contract period, the DTC was unable to meet its full ITO commitments to many clients across a range of boxes due to shortfalls in forecast availabilities.”

We find that hard to believe. De Beers has made a commitment to the Botswana government to sell to it some 10-15% of its output for domestic window sales. The Botswana government has created a marketing company, Okavango Diamonds, which, at any time, is allowed to purchase this entitlement. So far, it hasn’t done so. The arrangement doesn’t work retroactively – in other words, goods which Okavango has not purchased so far can be freely sold by the DTC. For this, and other reasons, I don’t “buy” the shortfall argument. It should have a few hundred millions in stock that had been earmarked for Okavango.

Let’s not overlook that Mellier’s policy, expressed in the company’s 2011 financial review, is that “De Beers produces in line with demand from our sightholders. … In the second half of the year [2011], as it became clear that the market was beginning to cool, we made the conscious decision to focus our resources on maintenance and waste-stripping backlogs. By addressing these issues when we did, we have put our mines in a strong position to ramp up production, as sightholder demand dictates, in 2012.”

Saying “we don’t have the goods” sounds better than admitting that its clients will not take the goods at current prices; it will also enhance the atmosphere of rough shortages. The DTC, at the June 2012 sight, reportedly also declined to sell some additional goods requested by some clients, which will further enhance the “shortages argument.” (I find this a rather strange decision since, when the DTC ultimately will sell these goods, it will be at lower prices.)

A sense of confusion and lack of direction at De Beers

Watching De Beers and listening to DTC sightholders and other stakeholders, one gets the sense that De Beers portrays a lack of direction, a lack of confidence and conviction among management and down to the sales team. Those attending one of the client and management functions at the last sight underpin the notion that all is not well among DTC decision makers. Some of this is understandable: the transition to Anglo American management and the move to Botswana create considerable anxieties among many employees. They are all waiting for Anglo.

We have written before that the company’s management has become much more of a spread-sheet exercise. Clients aren’t that important – and they are replaceable. What seems clear is that the “good old days,” when sightholders were enjoying double-digit premiums on the sight boxes, are something of the past. These days will not come back. That changes something in the relationship equation. One might say that, in the past, De Beers “bought” client loyalty as it was really worth it to be a sightholder. Now, De Beers needs to “earn” client loyalty – and they don’t seem to be making a great effort anymore.

While Anglo American decided to buy out the Oppenheimer family’s stake in De Beers, Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton and, most recently, Alrosa’s 51% shareholder, the Russian federal government, have all put up sale signs on their respective diamond businesses… Are these companies really selling the golden goose, or is it simply that the goose no longer lays golden eggs??!!”

Even though Mellier stresses in recent interviews that it is recognised that diamonds are “a different kind of commodity,” I am not sure that Mellier knows what that means or that I understand what he meant. Maybe it is our problem.

While Anglo American decided to buy out the Oppenheimer family’s stake in De Beers, Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton and, most recently, Alrosa’s 51% shareholder, the Russian federal government, have all put up sale signs on their respective diamond businesses. These changes affect nearly 70-75% of the entire rough diamond supplies. It was a surprise to many that the Oppenheimer family decided to move out of the business altogether. (If his family, especially his sister Mary Slack and her four daughters, needed money – he still could have kept a sizeable share in the business for himself and son Jonathan.)

These actions raise the basic questions of what the future holds for the diamond mining industry and what it will mean for companies in the downstream diamond businesses. Are these companies really selling the golden goose, or is it simply that the goose no longer lays golden eggs??!!

Companies managed by employees rather than owners

One must look beyond De Beers – and many of the industry changes we are witnessing are not of De Beers’ making. On rough pricing, the industry has already seen a pivotal shift in how rough is priced and sold. That is the industry legacy of the crisis. Diamond producers have come to believe that the best way to manage a slowdown is to keep the goods in the ground, something which other industries have also followed. There, the diamonds are safe, can be extracted when required, and don’t even run afoul with anti-trust regulators!!

What has undoubtedly changed for the worse is the perspective of the producers themselves. These businesses are no longer run by people who own them. Instead, the businesses are managed by professional managers appointed by the boards. That’s the main change we see now at De Beers, where, by tradition and by management contract, the Oppenheimer family ultimately made the final decisions.

These professional managers may or may not have diamond business experience. Their sole focus is the profitability of the company over the duration of their tenure, which might be between three to five years. For some of these managers, reducing rough production seemed like the golden wand that could help them push up volumes.

The “benevolent” producer does not exist anymore, with all the large producers purely focused on maximising their prices, rather than ensuring the basic health of the pipeline. A professional manager has to justify to his board that he is securing the best possible prices during the course of his tenure. He is not really concerned about whether his customers are really profitable or whether the producer is really the supplier of choice. That would be the problem of the next manager!!

Prices over sustainable levels

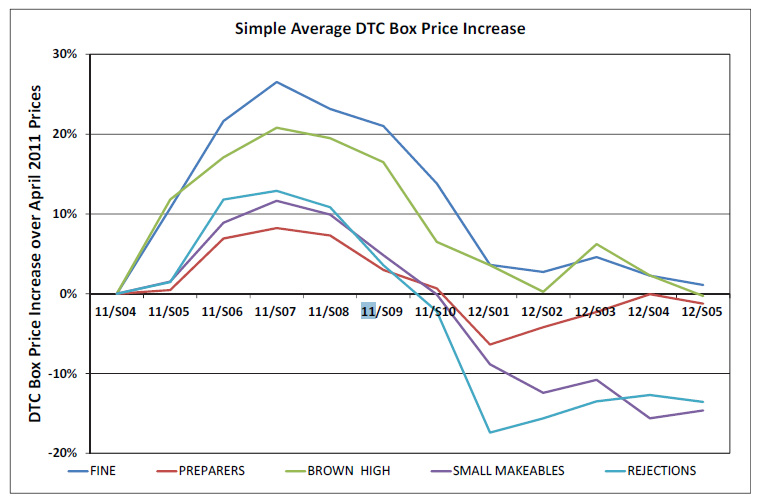

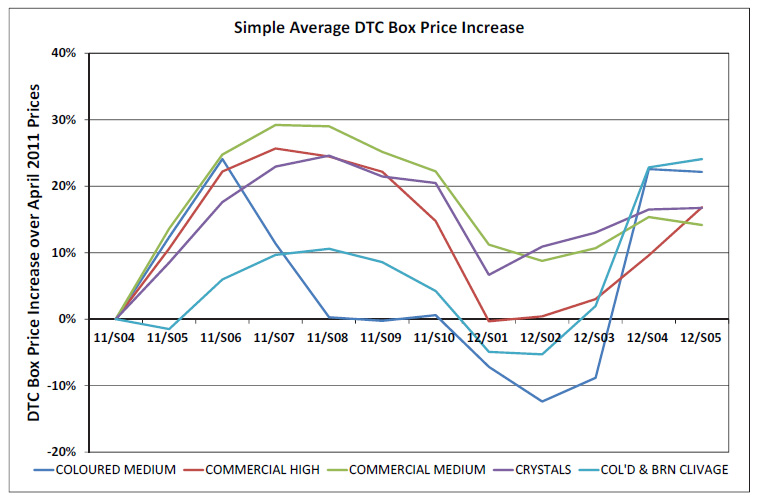

Looking just at the last 12 DTC sights or so, one can distinguish price movements in both directions ranging from 25% upwards to 25% or more downwards, depending on the boxes. DTC sight box comparisons are complex, as in many instances the composition of boxes have also seen changes – and if a box containing from four to eight grainers changes the ratio of sizes, this impairs the validity of comparisons. Nevertheless, we believe that our charts are broadly representative.

The following chart shows the five categories of boxes where DTC average prices were the lowest, when compared to the prices in April 2011.

This chart shows the five boxes where DTC average prices moved the highest, when compared to the DTC box prices from April 2011 to today.

In most of these boxes, it’s interesting to see that the average price seems to have actually increased by up to 29% between the first and the fifth sight of 2012.

We do express some caution. These prices are based on a simple average of individual boxes constituting each category. They do not account for the actual carats sold and, hence, may not necessarily reflect the actual mix provided within the boxes and across boxes. Hence, these might not necessarily reflect the average price achieved by DTC.

Russians followed DTC pricing policy. Their goods are also priced much above market – in same if not higher ranges than DTC. Alrosa’s product mix is different, more smaller and better quality diamonds, where prices moved up much more.

DTC prices peaked in July/August of 2011. At that point of time, most industry players considered DTC rough prices about 10% higher than what was sustainable. Over the course of nearly one year, polished prices have dropped about 15%, while DTC prices also seem to have dropped about 13%, which would mean that the current prices would also be about 10-15% above sustainable levels.

The prospects of De Beers

Looking at a crystal ball, what is the likely outcome for De Beers for its current supply and pricing policies? We believe that it is more than likely that:

- De Beers will lose market share to other producers.

- Management may not meet its profit targets – and staff may miss out on bonuses.

- De Beers may run into cash-flow challenges (if there are more sights where $100-$150 million is left on the table.) This requires reliance on Anglo American’s deep pockets.

- But the rudest awakening will come when De Beers’ management will wake up one morning to see that the goods left in the ground today cannot be sold at a higher price tomorrow.

Reducing rough supplies when you are not a near-monopoly is essentially a suicidal move, with other producers (read Alrosa, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Harry Winston Diamond Corp., Gem Diamonds, Petra, etc.) laughing their way to the bank. De Beers inevitably will change its course, as survival is a stronger instinct than ego, but the damage might be irreparable if the changes aren’t done sooner rather than later.

The market is heading for three difficult years – but De Beers will underperform other producers in terms of profits and will lose market share. In the diamond business, we are not still getting out of the last crisis, we are heading into a new one at full speed. True, that may not be up to De Beers. But De Beers is making sure that it is positioned in a worse place than other producers. This is in nobody’s best interest – nobody!