The Museum of Meenakari Heritage (MOMH), founded by renowned jewellery designer Sunita Shekhawat, is the first private museum in India dedicated to celebrating a local heritage craft. Spread over 3,000 sq. ft. the gallery is located in the newly built Shekhawat Haveli in Jaipur. The haveli’s Jodhpuri red sandstone facade and intricately detailed interiors, graciously house a craft that has shaped India’s jewellery history for centuries.

The museum is designed by Siddhartha Das Studio and curated by Dr. Usha R. Balakrishnan, a world-acclaimed jewellery historian.

MOMH brings together archival research and over 300 images sourced from leading global museums and institutions, which were used to create 120 masterful reproductions by the House of Shekhawat. Together, they trace enamel’s journey from Renaissance Europe to Mughal ateliers and, finally, Rajasthan’s royal courts. Unlike most museums, entry here is by prior appointment, offering visitors an intimate experience of India’s enamel traditions in the very city that nurtured them.

Here’s what Sunita Shekhawat had to say about what inspired her to undertake an ambitious project of monumental scale.

What inspired you to build a museum dedicated to Minakari, especially with no institutional or government funding?

Meenakari is a refined and intricate art form with deep cultural significance for India. It’s an art of immense beauty, yet so few truly understand it—for instance, why a kundan necklace is enamelled on the reverse, or how enamel colours breathe life into pure gold or gold alloys. I wanted to give this art the recognition it has long deserved. For me, the museum was a way to place this craft on the pedestal where it belongs. It was also my way of giving back to Jaipur and to the art of Meenakari art, which has given my family a legacy to protect.

Historically, India’s invaders claimed many of our treasures, but they could never take away our knowledge and expertise in the crafts. It is this very mastery that we have used to bring the story of Meenakari and enamelling to life through the museum.

While curating the museum, we discovered that the art form reached India through the Portuguese in Goa, and after that through the Persian artisans under Mughal patronage in northern India. I also realised that the colours we developed in our own workshops have contributed to enriching the journey of Meenakari. Something I would not have realised had I not looked at documenting Meenakari’s journey.

You’ve built this museum with great care, legal diligence, and your own investments, yet it isn’t monetised. Why?

MOMH was never about profit. It is a passion-driven legacy project—a way to celebrate and preserve Meenakari. Revenue matters, but only if it does not compromise independence or the integrity of the craft. We’ve deliberately avoided corporate tie-ups or government funding and maintained full ownership. Growth and maintenance of this museum will be controlled, deliberate, and thoughtful. Visits are by appointment; there is no ticketing system.

When did the idea for the museum first take shape, and how long did it take to realise it?

The museum has been our family’s vision for nearly ten years. It took us four years of research and work to make it happen. We sought permission from numerous museums to use their historical images and information, to trace the journey of enamelling from various parts of the world to India.

We were fortunate to have jewellery historian Dr. Usha R Balakrishnan, the curator of our museum, guiding us through the process. We had IP experts from around the world to secure photographs and usage rights. For the written content and editing, we were supported by an expert from The Met, New York.

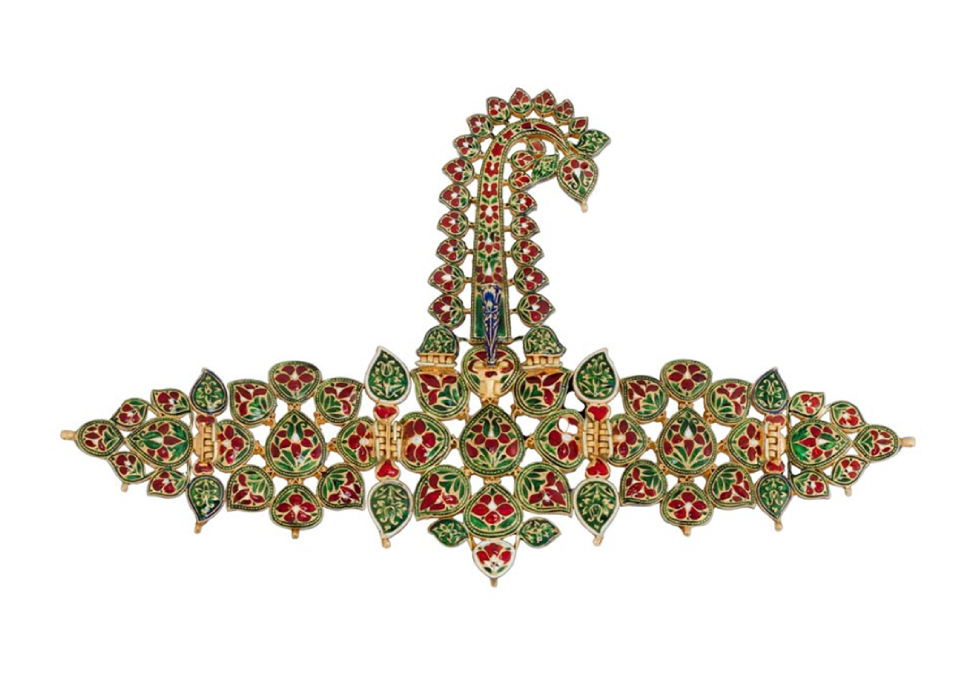

One highlight of our museum is the Nizam’s sarpech, reproduced by our karigars using a few photographs sourced from the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. After the museum opened, the director of the Houston Museum visited us and was deeply impressed by the precision and skill of our craftsmen’s talent, who created a near-identical sarpech in our workshops. Every material used for the reproduction was procured from Rajasthan only.

Tell us more about what went into documenting the journey of Meenakari in the museum.

We gathered over 300 images from more than 15 leading museums and galleries worldwide, including the British Museum, V&A, Art Institute of Chicago, MET, Aga Khan Museum, Hermitage, and Sotheby’s, tracing enamelling from Renaissance Europe to India. We created over 120 reproductions from the images and information, preserving archival motifs, styles, and histories of the craft.

We also wanted to dedicate a special section for the story of Meenakari’s history in India. The art form was traditionally executed on 24- and 22-karat gold in India because lower karats or alloys as canvas dilute the vibrancy of the enamel. We produced accurate examples of true Indian Meenakari. To preserve authenticity, it was essential to show the craft in its purest form, underscoring its value and importance for generations to come. The museum celebrates this depth, showing how enamel adds brilliance to gold beyond gemstones.

The museum currently showcases five key enamelling techniques, including cloisonné, champlevé, plique-à-jour, and basse-taille. It also highlights traditional Indian methods such as Ab-e-lehr, with a gold base engraved in wave patterns and transparent enamel; Boond-tila, featuring chased gold with translucent enamel; and Ferozi-zamin, an engraved gold base dominated by opaque enamel.

What’s the next phase for bringing Meenakari to a wider audience through the museum?

We plan to launch a Meenakari art residency in about two years.