As gold prices defy gravity, breaking records above $4,000 per ounce, the world’s mines tell a very different story — one of stagnation, red tape, and missed opportunities. In India, despite vast geological potential, gold mining remains a faint echo of its promise, with production hovering at just two tonnes against annual demand of 800 tonnes. While global giants like China push ahead with large-scale and artisanal mining, India’s ambitions are still largely untapped.

In this special feature, bullion analyst Sanjiv Arole explores the paradox of soaring gold prices and silent mines, and in an exclusive conversation with Charles Devenish, founder of Deccan Gold Mines, uncovers how innovative models like a Gold Bullion Royalty Fund could help India strike gold—literally.

During the monsoon, one sees an unusual gravity-defying Naneghat waterfall in the Western Ghats of Maharashtra. High winds push the water upwards, creating a reverse cascade. Gold, too, displayed its own version of a reverse waterfall. At the beginning of September 2025, gold was trading above $3,400 per ounce and seemed to be consolidating its position. Then it not only crossed the $3,500 mark for the first time but performed its own “Vertical Charlie” (in Air Force parlance) as it soared past the $4,000 per ounce level, breaking the all-time high for the 48th time in 2025 alone.

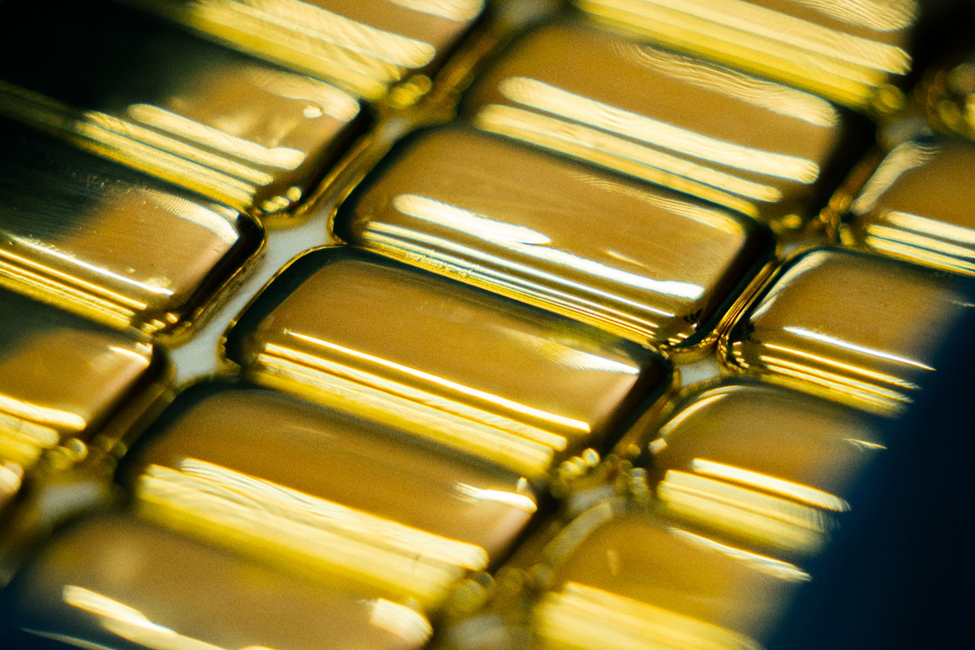

Gold, with silver tagging along, seemed in a tearaway hurry to scale fresh highs of over $4,000 per ounce, while silver aimed to reach $50 per ounce for the first time since 1980. However, spot gold not only crossed $4,000 on 8 October 2025 but also touched its latest all-time high of $4,381 per ounce on 17 October 2025. Silver, too, followed suit, rising to an all-time high of $54.52 per ounce on the same day (both intra-day).

In normal times, whenever gold or any precious metal prices rise, increased activity follows to capitalise on higher prices. However, despite a sharp rise in gold prices since 2020, gold mining has not witnessed any significant rise in production.

On the contrary, during the pandemic, gold production actually declined. In 2024, gold produced from mines rose by a modest 3%. The landscape of gold mining has changed over time — Australia, South Africa, and the US no longer host the largest mines.

Today, artisanal gold mines dominate the sector, with China leading from the front. In the mid-1990s, China’s gold production from its mines was around 150 tonnes. Last year, China remained the world’s largest gold producer at 380 tonnes.

China’s domestic artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector is somewhat unique compared to other countries. Unlike many nations where ASM is tied to poverty, China’s mines developed during a booming economy. The sector also features a greater diversity of minerals than anywhere else in the world. There is now a heavy Chinese presence in Ghana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Indonesia, and several Latin American countries, which have discovered new deposits through ASM. The Chinese footprint has, in many ways, redefined global gold mining.

Recent discoveries include a massive find in Hunan, China, estimated at 300 tonnes with potential up to 1,000 tonnes; a 125-km gold belt near Mecca, Saudi Arabia, expected to yield 200 tonnes; and an Odisha deposit in India with 20–30 tonnes potential, alongside ongoing explorations in several Indian states. New deposits have also been reported in Latin America and Pakistan, with smaller finds elsewhere extending existing mines’ life.

Indian gold mining sector

Geologically, India is similar to Australia and Africa, both having vast reserves of precious metals (gold, in particular) and diamonds. Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and its surrounding regions as well as parts of central India are believed to be rich in metal deposits. Gold has been mined at the Hutti Gold Mine and the Kolar Gold Fields. According to a Geological Survey of India, the country has 23.85 million tonnes of gold ore. The liberalisation era of the 1990s saw the mining sector being opened to the private sector and FDI too was permitted by 1994. As a result, De Beers, Rio Tinto, etc, evinced interest in diamond mining.

As far as gold was concerned one saw Deccan Gold Mines, Australian Resources (Geomysore), etc., put up their hand.

Mining in India is a lengthy process involving multiple stages—reconnaissance, exploration, excavation, and prospecting—before a company can obtain a licence. As it falls under both state and central jurisdictions, red tape often delays progress. De Beers exited after years of effort, and Rio Tinto quit the ecologically sensitive Bunder project in 2017, handing assets to the Madhya Pradesh government.

A private firm was set to begin gold production at the Jonnagiri mines in Andhra Pradesh, but faced fresh hurdles. In December 2022, reports indicated that Essel Mining and Industries, a subsidiary of the Aditya Birla Group, also struggled to operationalise the Bunder diamond mine previously abandoned by Rio Tinto.

Currently, India’s gold produced is around 1.5-2 tonnes from the Hutti Gold Mines. After the closure of the Kolar Gold Fields in 2001 Indian domestic gold has plummeted to around 2 tonnes against an annual gold consumption of around 800 tonnes.

Since its founding in 2003, Deccan Gold Mines has attempted to revive India’s gold mining industry, but without success. Most deposits lie in remote forests or hilly terrains, drawing strong opposition from environmentalists. It is vital to create awareness of mining’s economic value — as seen in Botswana, where Debswana contributes nearly 80% of national revenue. Responsible mining can generate jobs, boost regional economies, and coexist with environmental and agricultural development through open dialogue.

In an exclusive interview, Charles Devenish, founder of Deccan Gold Mines, who has spent nearly three decades in India, shares how he continues to pursue his dream of turning the country into a gold-mining superpower.

Do you have any plan of action on how to procure funds to finance gold mining in India?

Charles Devenish: Perhaps the creation of a Gold Bullion Royalty Fund for India, one that lends physical gold to develop new mines, could help resolve this long-standing issue. With most foreign mining companies having exited, the country must now rely on its own resources. The loan would be repaid through the mine’s gold production, while the Royalty Fund earns royalties for the mine’s lifespan and investors receive steady annual dividends on an asset once lying dormant.

Could you elaborate on this concept of a Gold Bullion Royalty Fund?

The ultimate beneficial business deal for India could be a Gold Fund, which mobilises India’s “Billions of Black Gold Dollars”.

The concept of a gold loan for mining was first developed in Australia to finance proven gold resources in the ground. Gold was borrowed from the Reserve Bank of Australia, sold in the market, and the proceeds were used to build the mine. The loan was later repaid from the mine’s future gold production. Even the Reserve Bank benefited, earning about 3% interest on an otherwise non-earning gold asset.

A more prudent approach could be the creation of a Royalty Gold Fund, built from both legally and undeclared gold held within India. Holders of such gold could be incentivised to participate in future gold mining projects. This mobilised gold could then be used to finance and develop hundreds of new Indian gold mines through the Royalty Gold Fund.

Like China, India can rope in hundreds of small artisanal gold mines that could be listed on the BSE. It could also adopt the successful Australian model for Gold Loans. Australia built a very successful Tax Free Gold Mining Industry, but it required a bit of creative thinking and simple logic about understanding basic human greed.

How could it benefit India overall?

The major advantage for India would be a sharp reduction in gold imports as the new “Indian Black Gold” enters the market. Another key benefit would be the ability to finance hundreds of junior start-up companies, which could be listed on the BSE, similar to Deccan Gold Mines Ltd. These smaller firms could gradually dominate India’s mining and mineral exploration space, preventing large foreign corporations from controlling the nation’s mineral wealth.

The discussion with Charles naturally leads to a re-examination of India’s gold mining regulations:

Regulatory Framework

The inability of even the MMDR Amended Act, 2015, to set the ball rolling in the country’s gold mining has led most stakeholders to seek an amendment to the Act. The fact that foreign mining companies have exited operations indicates that the country’s mining laws still need reform. In his paper, ‘Urgent Need to Amend the MMDR Amendment Act-2015’, Dr. V.N. Vasudev, a renowned Indian geologist and mineral exploration expert, stated that while the Act introduced auctions to make mineral licensing more transparent, the system unintentionally discouraged private investment, especially from Junior Exploration Companies (JECs). The auction-only model is unsuitable for precious metals and diamonds.

The proposed solution is to introduce a dual-mode system: Auctions for Mining Leases (MLs) with certified, proven resources. First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) model for Exploration Licences (ELs), Composite Licences (CLs), and Artisanal Mining Licences (AMLs). This will encourage foreign and domestic private investment; focus on critical minerals, precious metals, and strategic minerals; empower MSMEs in mining and support rural economic development; and support the Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India).

It’s also necessary to understand that exploration is not the same as mining. Exploration involves entrepreneurs taking risks to locate deposits that are technically and economically feasible to extract. It is also the miner’s right to reap profits towards the risks taken during exploration and face the prospects of failure.

Perhaps mining bureaucrats should engage more closely with geologists to understand the complexities of gold mining. Only then can Charles Devenish’s vision — of seeing India regain its position as an economic superpower by following the gold-mining path once taken by Emperor Ashoka — truly be realised.