In a quaint workshop, somewhere in Johari Bazaar, Jaipur, I first heard the term Paanidar … Paani means water in Hindi. It’s an expression commonly used in India to describe the finest emeralds, with the luminosity of the stone equated to being saturated with the purest water. At the recent auction of Zambian emeralds by Gemfields that concluded in Singapore, I got an opportunity to check the proceedings up close. Here are my takeaways.

In a land far away, there lives a tribe of humans who speak a strange language. They use big words, bizarre tools, live away from their families, surrounded by crocodiles, elephants, lions and a gigantic waterfall. The land is called Zambia, and this unusual species, known as ‘geologists’, are part of a tribe called Gemfields.

While the story of Zambian emeralds today seems to be synonymous with Gemfields, Indian manufacturers have been sourcing emeralds from Zambia since the late seventies. At that time the sector was quite fragmented and the on-ground situation mercurial. The first auction by the government, under Reserve Mineral Corporation, was held in 1982. There were only three to five grades of rough emeralds. Due to this, considerable time at the auction was first spent sorting onsite by customers, before analysing possible yield or competition. The strategy for bidding was similarly fragmented and short-term, depending on the quality of the lots presented at that particular auction. On the plus side, the occurrence of good quality stones in lower quality lots was frequent. While this was beneficial for manufacturers, it resulted in considerable losses for the Zambian government.

In 2008, Gemfields took over Kagem Mining Ltd. continuing the public-private partnership (75:25) established by the previous owners. At that time, production was sporadic, infrastructure inadequate, and pilferage frequent.

The company got to work upgrading the infrastructure, improving security, increasing production. However, to maximise yield from each gram of emerald, they had to do more.

They had some stockpile from previous years, and as a result of the current development of the mine there was increased production of emeralds. At this stage, they were at a crossroads: should they go to market immediately or take time to understand the emerald production. After an initial period of difficulty and experimentation with a basic auction format, they decided to wait.

The increasing depth of production allowed Gemfields to create an initial blueprint for grading emeralds as per size, clarity and colour; and to a lesser degree, shape and recovery.

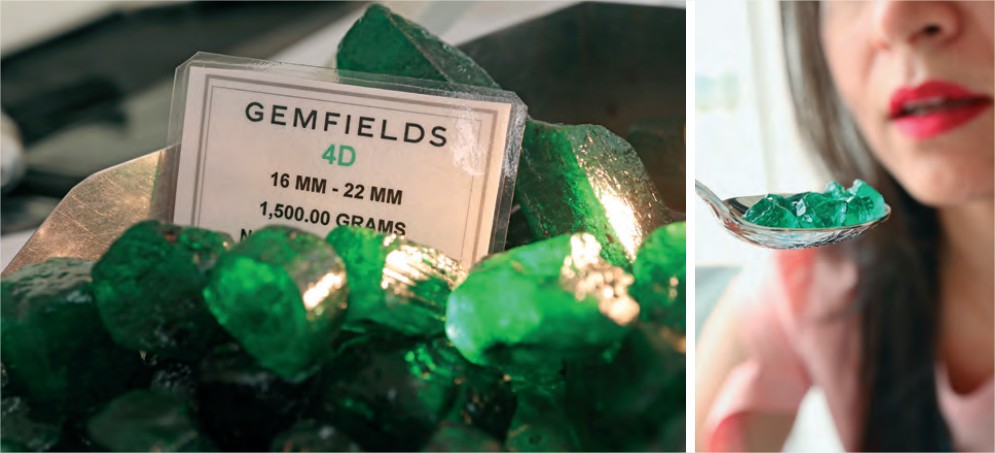

The first formal auction was conducted in London in July 2009 where the market was presented with 180 varying grades of emeralds versus the 4-5 they were used to before. Over the next two years, the Gemfields team worked hard, continuously analysing the production and refining the grades. Today, the company provides customers with 213 grades across high and commercial quality emeralds. What’s impressive is not only the expansive nature of categorisation but the surgical consistency of the system year on year. The company achieves this with large-scale production, combined with incredible discipline in sorting. Inspired by Gemfields’s success, other mining companies in the sector have also created their versions of the grading system, some more successful than others. The challenge is not the creation of a system but maintaining the consistency, for which, one of the key ingredients is the scale of production. At Kagem, it’s a 1 in a 5-million-part situation, which means for one spoon of emeralds, one must move 5 million spoons of rock.

The emerald auctions are segmented, with the commercial grade material auctioned in Jaipur, and premium grade in Lusaka, Zambia. This year, Gemfields decided to move their premium grade emerald auction to Singapore, an emerging hub for mining companies. The country offers fantastic infrastructure, top-notch security, and professional service.

Additionally, given Singapore’s proximity to India, which represents 95% of Gemfields’s emerald clients, it’s more accessible than Lusaka.

In fact, in his opening remarks, Dr Mulenga, chairman of Kagem Mining Ltd. said, “I would like to start by thanking you for your continued support. Some of you have been with us since we started the company. Today, as per our discussion in Lusaka, we have fulfilled your wish and brought the auction to Singapore. Our commitment to mutual development and benefit is nonnegotiable and 100%!”

The excitement among clients this time was not only because of the beautiful venue but also the world famous INKALAMU Emerald. Day 1 of the auction saw many spend time viewing the 5,655-carat ‘Lion Emerald’. Some, seriously evaluating for bidding, and others taking photos for friends, family and social media. Irrespective of the reasons, the reactions across the board were quite similar – of wonder, admiration, and respect for its natural beauty gifted by Mother Nature.

To quote Sean Gilbertson, CEO Gemfields, “The INKALAMU Emerald is the single most expensive emerald to come from the largest emerald mine in the world. As far as our records are concerned, in the 35 years that Kagem emerald mine has been operational, this is one of the finest crystals to come out of the ground, 450 million years old. The emerald is also remarkable in that, thanks to the GUBELIN laboratories in Switzerland, it contains the new Nano-particles Provenance Proof technology. This means, once this gemstone is cut and polished into smaller gems, one can track and trace the new pride of lions for decades to come, all the way back to the mine of origin at Kagem in Zambia.”

The winning bid for the INKALAMU was by Diacolor’s Rajkumar Tongya, who beautifully described the specimen: “I’ve been buying emeralds from all over the world, and this is one of the best pieces I have come across. It has a homogeneous green colour, with extraordinary lustre and because of its broad shape, it has been named INKALAMU or the Lion. On closer inspection, we can see that the black schist rock is only a cover and underneath it’s all green crystal material, which is very difficult to find. It’s an unbelievable, amazing, incredible, extraordinary, fantastic piece.”

Listening to the passionate explanation by Tongya, one can understand why he has no desire at the moment to cut it. Last year, Diacolor also won the bid for the INSOFU Emerald, which weighed 6,100 carats. I don’t know about you but I for one look forward to seeing how the Diacolor Emerald Game Reserve grows over the coming years!

Besides, the INKALAMU, the real revenue drivers were not just the top schedules but also the medium quality lots. Overall, this particular auction delivered excellent material to the market along with much-needed quantity. The response was quite apparent as bidders repeatedly viewed the lots. This time, the format was also slightly different with Gemfields splitting the event into two auctions. In this manner, clients who didn’t win in Auction 1, had the opportunity to be more aggressive with their bid in Auction 2.

Traceability, responsible sourcing, transparency, are no longer mere marketing tools and buzzwords. These are real demands from brands and consumers in the gem and jewellery sector. On the sidelines of the auction, Dr Daniel Nyfeler, managing director, GUBELIN laboratory Switzerland, also gave a detailed presentation on their Provenance Proof Initiative, which encompasses an array of technologies designed to bring increased transparency at every step of the value chain. An integral component is the Emerald Paternity Test based on nanotechnology. All Emeralds in Auction 1 and some in Auction 2 contain nanoparticles with specific information about Kagem Mining Ltd. GUBELIN claims, due to the nature of the technology, the nanoparticles will survive the cutting, treating, polishing, and cleaning process. This technology delivers insofar as providing brands with the confidence they need, to support claims of responsible sourcing, and it is a big step in the right direction.

However, like with all new technologies, it may still require some refinement. I say this because when a customer wants to test their emerald, the extraction of the nanoparticles may disturb the oiling. While one may easily argue that the probability of the request for the test is low, and the stone can easily be re-oiled, it still leaves some unanswered questions in the market.

Nonetheless, it was encouraging to observe the very animated discussion following Dr Nyfeler’s presentation. A sign that the market is interested, engaged and while still a bit sceptical, willing to listen, absorb and reflect on the possibilities.

The success of any gemstone is dependent on consistent supply. Unlike the retail sector that can hold stock, the manufacturing segment continuously requires material to keep the wheels turning. Gemfields’ entry in the market with both emerald mining in Zambia and ruby mining in Mozambique has been a game changer in increasing supply. Additionally, they are focussed not only on responsible practices on-ground, but particularly in their choice of partners who are invited to bid at their auctions. Beyond financial, their criteria are based on a high standard of good governance, quality working conditions and infrastructure, resulting in the establishment of something more than responsible mining, a trustworthy eco-system that delivers from mine to market.