Supply-demand and pricing dynamics have pushed the trade into a sharper dispute over how synthetic diamonds should be described, graded and distinguished from natural ones.

“It’s synthetics,” an audience member shouted during a panel at the CIBJO Congress in Paris. “Excuse me, I’ve been badly trained,” acknowledged David Kellie, the outgoing CEO of the Natural Diamond Council, who subsequently was careful not to use the term lab grown. Terminology has emerged as an important battleground, and it is likely to remain one as the trade pushes for language that clearly separates the product from natural diamonds.

The Union Française de la Bijouterie, Joaillerie, Orfèvrerie, des Pierres et des Perles (UFBJOP), which hosted the congress, has been at the forefront of the push for more accurate wording.

“Laboratory grown is misleading because the diamonds are manufactured in a factory,” said UFBJOP executive president Bernadette Pinet-Cuoq. “It is essential to question the acceptability of the word laboratory, and to reestablish a clear boundary between natural diamonds and synthetic ones.”

Earlier this year, the French government upheld its decision to use the term synthetic when describing factory-created diamonds. Officials cited a 2022 public consultation showing that most industry and consumer respondents supported keeping the term for clarity and consistency. The move counters criticism from a local politician who argued that synthetic is misleading and carries an unfair stigma in the context of luxury jewellery.

For its part, the Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC) has recommended adopting the mandated definition, nomenclature and guidelines for diamonds specified by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC). These require any businesses selling synthetics to qualify the word diamond with terms such as “cultured,” “laboratory-created” or “laboratory-grown.”

In a Special Report for Diamonds published ahead of the congress, members of CIBJO’s executive revisit the organization’s 2010 decision to accept terms like “lab-grown” as synonyms for “synthetic.” The authors argue this blurred boundaries and lent synthetics undue legitimacy—particularly through use of the 4Cs in grading. They also called for revisions to CIBJO’s Diamond Blue Book to establish clearer terminology, restrict the 4Cs to natural diamonds, and strengthen consumer transparency.

Labs Weigh In

The debate over terminology reflects the broader split within the trade about how to handle the synthetic–natural divide and where the market is heading. That split was most visible in the contrasting approaches taken by the major grading laboratories.

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) ended its use of traditional colour and clarity grading for synthetic diamonds, replacing it with “premium” and “standard” quality descriptions. The shift reflects the narrow quality range of most lab grown goods and aims to create a clearer distinction from natural stones, the institute said in May.

HRD Antwerp, a subsidiary of the Antwerp World Diamond Centre, went further by announcing it will stop certifying synthetic diamonds from 2026. The organisation said the move is intended to help consumers more easily tell natural and synthetic stones apart.

The International Gemological Institute (IGI) took the opposite view, reaffirming its use of the full 4Cs for synthetics. It argued that consumer demand for lab grown diamonds calls for maximum transparency rather than reduced detail.

Clear Differentiation

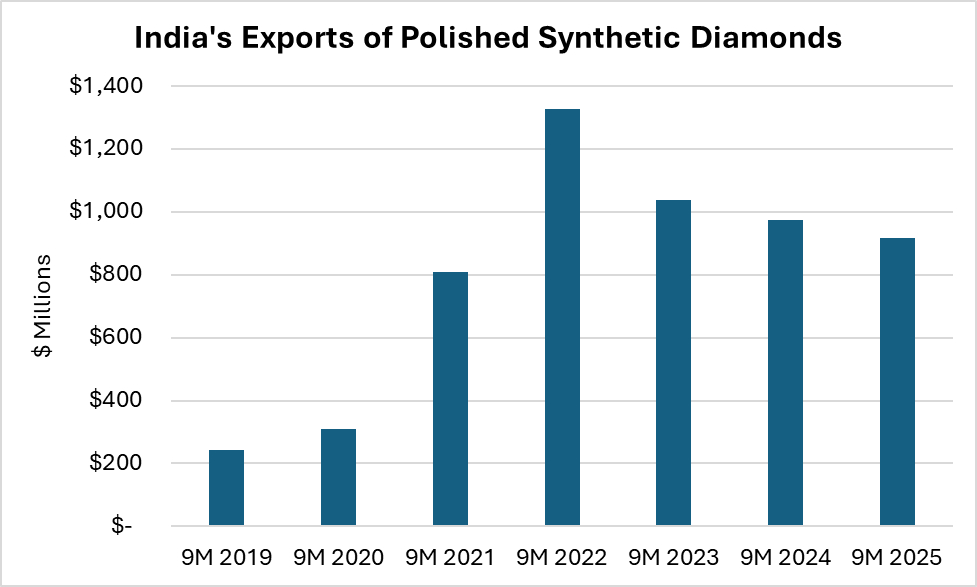

Meanwhile, the value of lab-grown diamonds continue to fall amid rising supply. India’s exports of polished synthetic diamonds slipped 6% to $916 million in the first nine months of the year, according to data published by the GJEPC.

Wholesale prices dropped 37% year on year in the third quarter, according to Edahn Golan’s LGD Wholesale Price List, indicating that India, the largest producer of CVD goods, supplied higher volumes at lower prices during the period.

Retail prices fell 14% year on year in the third quarter, which, while at a slower pace than the wholesale decline, indicates that retailer margins remain relatively strong for now.

That cushion may come under pressure as many expect retail prices to adjust more sharply as discrepancies across different sales channels become clearer to consumers.

The more prices diverge, the more critical it becomes for shoppers to understand exactly what type of product they are purchasing.

These pricing inconsistencies only heighten the need for clear, honest terminology. As the gap between natural and synthetic diamonds widens on value, origin and market behaviour, the trade cannot afford language that clouds the distinction for consumers.

Clear definitions have become one of the few tools the industry can rely on to reduce confusion as the market fragments. Pinet-Cuoq urged the broader industry to follow the French example.

“The French decree [from 2002] defines a diamond as synthetic when it is man-made, and therefore a diamond that is not man-made is natural,” she said. “That is our linguistic standard, which the authorities have confirmed. It is clear and avoids any confusion.”

Others will challenge the French position, but it is gaining traction among natural diamond advocates, ensuring that the debate over what to call a diamond will carry into the year ahead.

Avi Krawitz is the Founder of ‘The Diamond Press’ and a leading content creator and consultant in the diamond industry. He is widely recognised for his insightful analysis and storytelling, offering clarity to both industry professionals and curious consumers navigating a complex and evolving market. See more of Avi’s work at www.thediamondpress.com