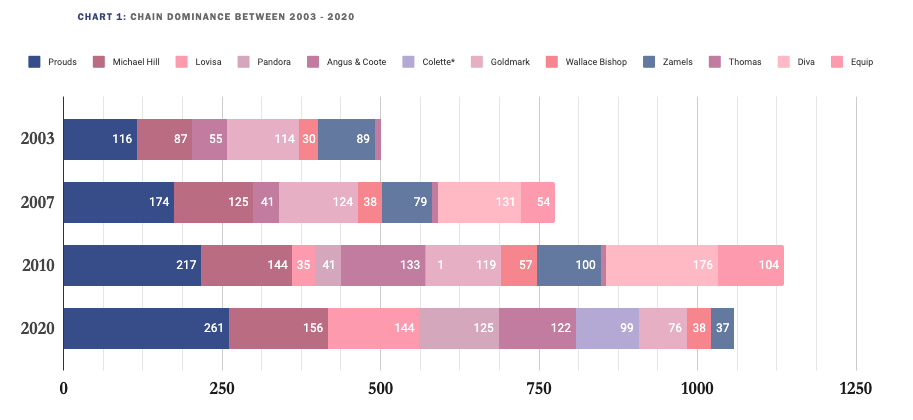

There is little doubt the past 10 years have led to significant change in the Australian jewellery landscape – yet analysis of the data by Jeweller shows a number of surprising trends and stories.

Australian jewellery retailing has undergone significant evolution over the past decade, but, surprisingly, the changes are very different to what was expected when Jeweller published its last State of the Industry Report in 2010.

A decade on from Jeweller’s first State of the Industry Report, the jewellery retail industry – mirroring the broader retail sector – has undergone momentous change.

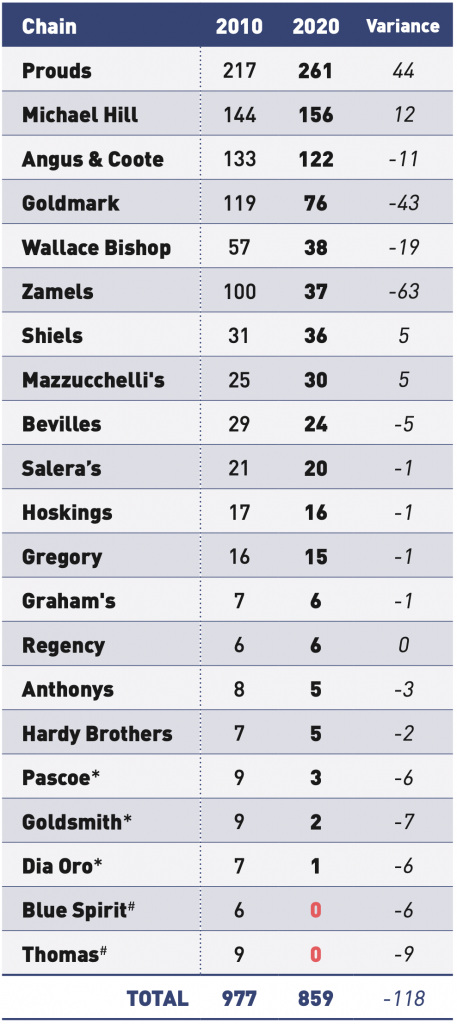

Yet over the past 10 years, fine jewellery chain stores have remained relatively resilient, at least in terms of store numbers.

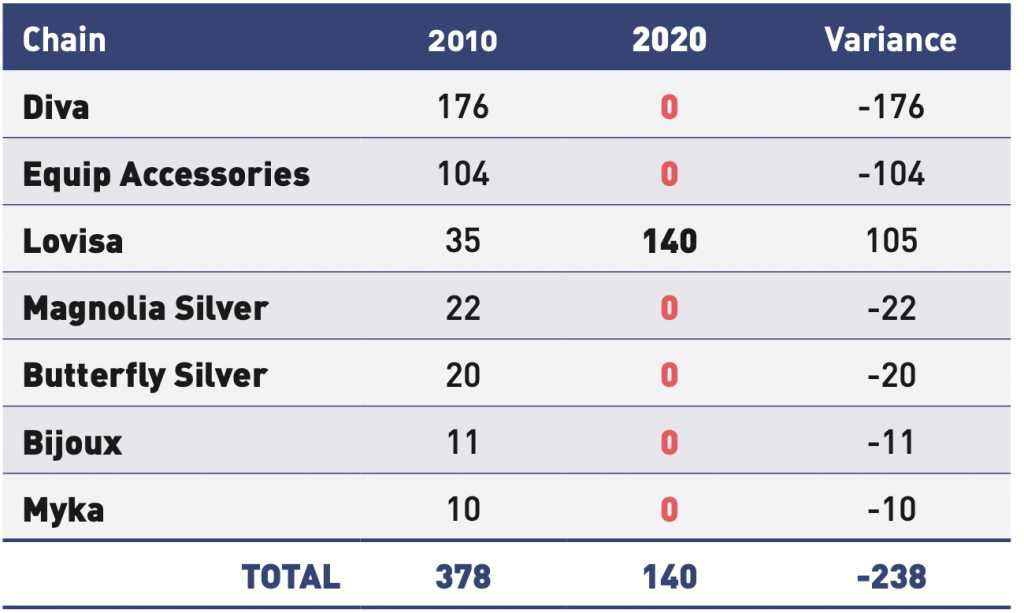

However, the same cannot be said for the fashion jewellery category!

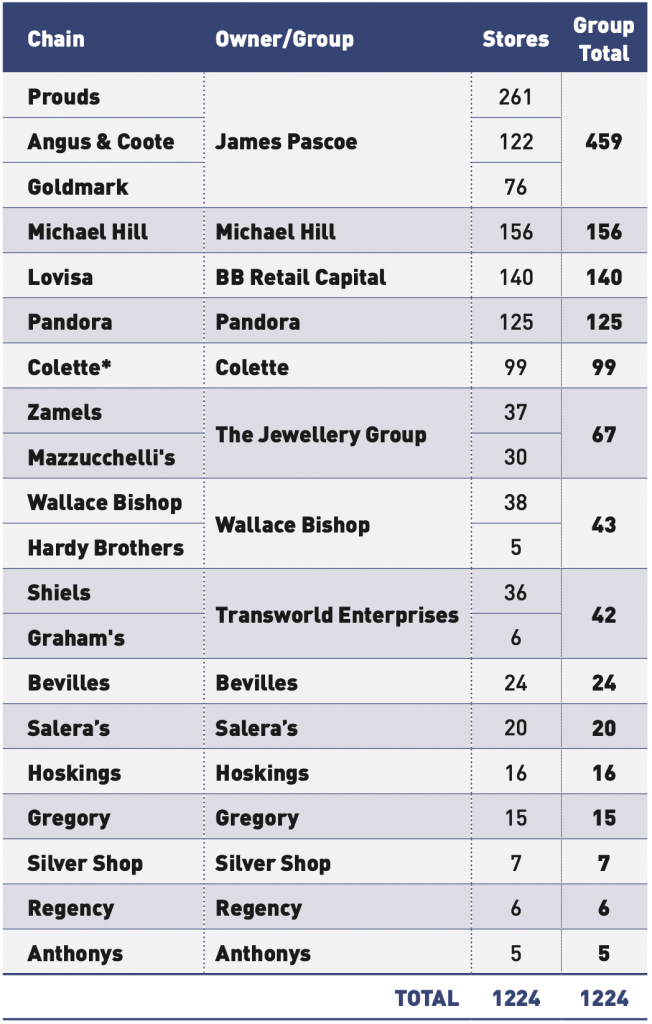

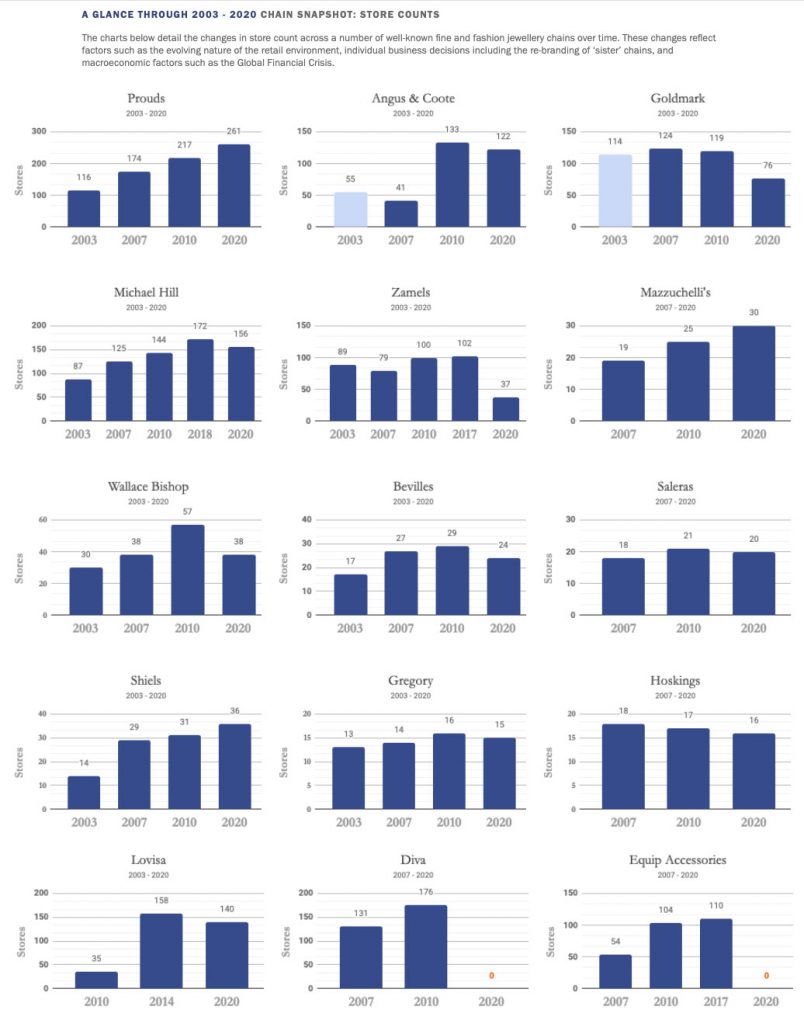

There were 21 fine jewellery chain store ‘brands’ in 2010, operating a total of 977 stores nationally. On a like-by-like basis, by 2020 that number had declined by 118 stores to 859, representing a 12% reduction in total store count.

That contraction could be considered small when compared with the performance of other consumer categories.

Some fine jewellery chains – such as Prouds and Michael Hill – managed to increase overall store numbers, while others marginally decreased.

Only two ‘names’ entirely disappeared from the list: Blue Spirit, a lesser-known small franchise, which operated six stores in 2010, and the high-profile Thomas Jewellers, with nine stores.

James Thomas founded Thomas Jewellers in 1896 in Ballarat. After 121 years of operation, the Thomas family decided to close its iconic Bourke Street Mall store in Melbourne in October 2017, as well as the Warnambool, Wagga Wagga, Albury, Shepparton, Bendigo, Ballarat and Geelong stores. In contrast, of the seven fashion jewellery chains listed in the State of the Industry Report (SOIR) 10 years ago, only one remains – six closed their physical stores.

The proverbial ‘last man standing’, Lovisa, has grown from 35 locations in Australia to 140 over the past decade, following the liquidation and closure of major competitors and smaller fashion jewellery chains alike – including its sister chain Diva.

The ‘downfall’ of the six fashion jewellery chains means that of the 378 stores that were operating in 2010, 343 no longer exist.

Demise of fashion chains

For the purpose of research and a report, it is necessary to create definitions in order to accurately measure and compare results across categories and over time.

Therefore, a ‘chain’ is defined as a group of five or more jewellery stores trading under the one (brand) name, with one ownership entity – a person or company – co-ordinating buying and marketing activities across the group. It could include a franchise operation.

In addition, Jeweller notes that a chain store usually has central management and standardised business methods and practices and will purchase product from both local suppliers and/or import its own product.

In 2020, Lovisa is the largest fashion jewellery chain operating in Australia. The ASX-listed BB Retail Capital, founded by retail entrepreneur Brett Blundy, owns it.

Lovisa’s current store count is 140; however, an article published by Jeweller in May 2014 detailing the closure of Lovisa’s 176-store sister chain Diva – also owned by BB Retail Capital – noted that Lovisa had 158 stores across Australia.

Therefore, even though Lovisa has had an impressive increase of 105 stores since 2010, it has rationalised its store count over the past few years by closing at least 18 outlets.

The demise of Diva is interesting. It was launched in 2003 by husband and wife team Colette and Mark Hayman, and within two years it had expanded to 83 stores. It was sold to BB Retail Capital in 2005.

By 2007, a further 72 stores had been opened, bringing to 131 the total retail outlets in Australia.

Diva operated a further 369 stores overseas, primarily targeting teenage girls, while Lovisa promoted itself as being able to “fill the void for high quality, fashion forward and directional jewellery.”

In 2010, and after a three-year absence from the industry due to a non-compete clause in the sale of Diva to BB Retail Capital, Colette Hayman launched a new fashion jewellery and accessories store, eponymously named Colette Accessories.

The first Colette Accessories store opened in Sydney’s CBD and, at the time, Hayman boasted that they would have 120 stores within three years. By 2014, the store count had reached 102 across Australia, with a further 18 overseas.

In contrast, of the seven fashion jewellery chains listed in the State of the Industry Report (SOIR) 10 years ago, only one remains – six closed their physical stores… The ‘downfall’ of the six fashion jewellery chains means that of the 378 stores that were operating in 2010, 343 no longer exist.

However in February, the company – which had been renamed Colette By Colette Hayman – was placed into administration.

At the time of publication, its 99 Australian stores, along with 41 New Zealand stores, remained in the hands of Deloitte Restructuring Services as the administrators attempted to re-capitalise or sell the business.

Diva and Colette are not the only large fashion jewellery chains to have found the going tough over the past decade.

Other closures

Butterfly Silver, a fashion jewellery business established in 2002, operated 20 stores in 2010. It collapsed in March 2018 closing all locations. However, Hoskings subsequently acquired the e-commerce business butterflysilver.com.au.

Equip Accessories, which featured in the 2010 SOIR with 104 stores, was liquidated in 2017. It had expanded to 110 Australian stores, all of which were closed.

The other three fashion chains that didn’t survive the decade with bricks and mortar locations were Magnolia Silver, Bijoux, and Myka.

In total, and along with Butterfly Silver, they represented 63 store closures. Magnolia Silver and Bijoux now operate as online-only businesses.

On the other hand, Silvershop, which was founded in 1999, has now expanded to seven stores in Queensland making it a small chain.

This collapse of 343 fashion jewellery stores, along with Colette’s 99 stores currently being in the hands of administrators, leads to the question: why has the retail landscape changed so drastically over the past decade for the lower end of the market?

The answer likely lies in more strenuous competition from online incumbents and new entrants, given that low-margin, high-volume fashion jewellery is more suited to internet sales than higher-value, low-volume fine jewellery.

Further, and more importantly, the continual increase in shopping centre tenancy costs – particularly per-square-metre rents – has resulted in an unsustainable business model, especially when ‘rent’ includes a percentage of sales.

This structure further reduces the margin on already low-margin items.

The collapse of 343 fashion jewellery stores, along with Colette’s 99 stores currently being in the hands of administrators, leads to the question: why has the retail landscape changed so drastically over the past decade for the lower end of the market?

Fine jewellery chains’ resilience

If one considers the long list of apparel and accessories chains that have collapsed over the past five years – including Roger David, Marcs, Ed Harry, Rhodes & Beckett, Bardot, and Jeanswest, among others – as well as international chains which have withdrawn from the Australian market, such as Topshop, Esprit, Jigsaw, and Karen Millen, fine chains have been surprisingly resilient.

Michael Hill Australia has expanded throughout the past decade, with 12 more stores in 2020 (156) than it had in 2010 (144).

However, those figures belie the fact that the company went through major upheaval when it exited the US market in 2018, closing nine stores.

At that time, the Australian store count had reached 172, which means that since 2010, when its store count was 144, it opened as many as 28 stores to February 2018 – yet in the ensuing period it has closed 16 stores (see chart right).

Michael Hill experienced a number of other ups and downs. The ASX-listed company decided to expand its ‘brand’ offering by establishing a new retail chain in 2014 called Emma & Roe – named after founder Sir Michael Hill’s daughter Emma and his wife’s maiden name, Roe.

The new stores attempted to specialise in ‘demi-fine’ charms, bracelets, necklaces, earrings and stackable rings.

The concept was trialled for 18 months, beginning in five Queensland stores in 2013 under the Captured Moments brand. After receiving “encouraging results”, the company opened its first Emma & Roe concept store in Mackay, Queensland, in April 2014.

Even though the number of Emma & Roe stores quickly increased, the venture ultimately proved unsuccessful. By June 2018 then-CEO Phil Taylor announced the closure of all 36 stores.

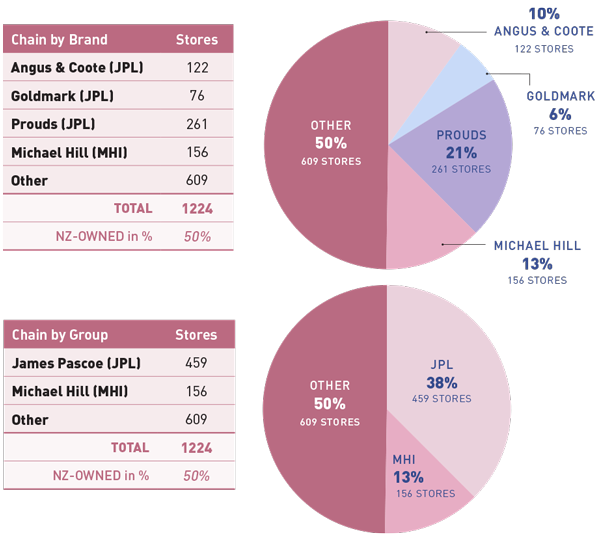

The ‘big boy’ of the Australian jewellery industry, James Pascoe Ltd (JPL), the owner of Prouds, Goldmark and Angus & Coote, remains the largest group, as it was in 2010. Since then it has had a net loss of only 10 stores, or 2%, declining from 469 to 459.

While the result is impressive, like Michael Hill, the company has rationalised its store mix and footprint across Australia. Prouds increased its presence by an impressive 44 stores since 2010 (from 217 to 261), yet 43 Goldmark stores were closed (falling from 119 to 76) during the same period while 11 Angus & Coote stores got the chop.

Myles Norman, general manager JPL, confirmed that some of the Angus & Coote and Goldmark ‘closures’ were stores that were converted to, and re-branded as, Prouds.

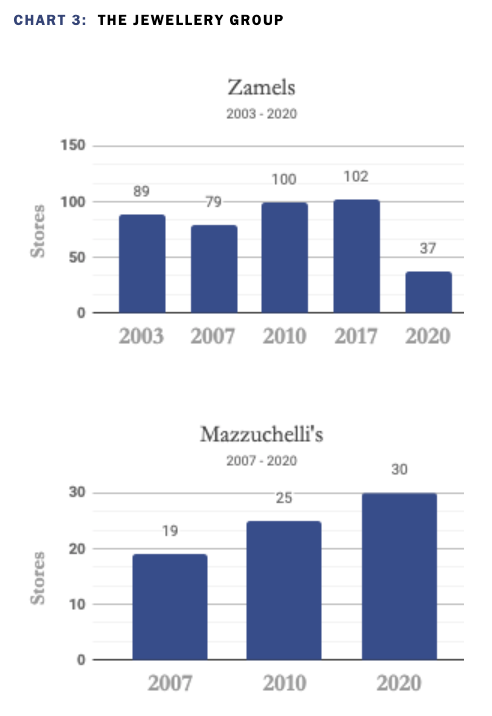

Decline of Zamels

However, the story is not as positive when it comes to The Jewellery Group, which owns Zamels and Mazzuchelli’s.

In 2010 Zamels was Australia’s third-largest jewellery chain with 100 retail stores; however, by June 2020, a whopping 63 Zamels stores had closed. During the same period The Jewellery Group also closed two single store ‘brands’, Vivien’s and Budgens.

On a brighter note, Mazzucchelli’s had increased from 25 stores in 2010 to 30 in 2020, most of which are new locations, with one Zamels store (Chadstone, in Melbourne) being converted to Mazzucchelli’s. As a result, The Jewellery Group is now less than half the size it was in 2010, operating 60 stores, down from 127.

Many of the problems facing Zamels can be traced to the 2007 sale of the 53-year-old family business to Quadrant Private Equity. At the time, speculation valued the deal at between $75 million and $100 million.

With a total of 67 stores, The Jewellery Group is half the size it was in 2010.

However, when the takeover was completed, industry sources suggested the final sale was closer to $48 million – a figure that many believed was still excessive.

Five years later, that assessment was seemingly proved correct when Quadrant sold The Jewellery Group to one of the world’s largest jewellery manufacturers: Mumbai-based M Suresh Group DMCC.

In November 2017, Jeweller reported: “In a stunning depreciation, Quadrant is tipped to be offloading the group for less than $20 million – a loss of around $30 million in just over four years.”

At the time of the second sale, industry pundits questioned the logic of an Indian jewellery manufacturer operating an Australian-based retail chain, which then accounted for 102 Zamels and 27 Mazzucchelli’s stores.

Zamels had also encountered problems with its brand image in 2012 when it was fined $250,000 by the Federal Court after being found guilty of misleading consumers about the savings to be made during an extensive sales period.

Unfortunately for The Jewellery Group, it was the second time that Zamels had been targeted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) over two-price – also known as ‘was-now’ – advertising.

In 2006 the ACCC launched legal proceedings against the then-family owned Zamels in regard to its 2005 Christmas catalogue. The Federal Court found that Zamels had not sold the items at a strikethrough (was) price for a reasonable period prior to the sale.

This ACCC double-whammy might also have affected the Zamels’ business model which was based around ‘was-now’ advertising; its retail marketing and pricing strategies were changed and which, ultimately, could have impacted trading levels.

Mid-sized chains up and down

The mid-sized retail chains present an interesting scenario, with developments that might have seemed unexpected a decade ago.

In 2010, Wallace Bishop was Australia’s sixth-largest fine jewellery brand, with 57 stores. It also operated seven Hardy Brothers stores after acquiring the iconic brand in 1997.

With a combined total of 64 group stores, Wallace Bishop was the fourth largest group after JPL (469 stores), Michael Hill (144) and The Jewellery Group (127).

The high-profile Queensland retailer has since closed 19 stores as well as two Hardy Brothers stores.

In 2017, the proud family business celebrated its centenary. At the time, CEO Stuart Bishop – the grandson of founder Wallace Bishop – told Jeweller that the retailer had overcome many obstacles over the years, including two World Wars, the Great Depression, economic downturns and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

“We have tackled and embraced the rise of the shopping centre during the 20th Century and of course more recently, the internet revolution,” Bishop added.

However, despite the business’ long history of resilience, it is fair to say that management didn’t expect to see anything like the coronavirus pandemic that has caused a worldwide economic crisis.

Still, Bishop told Jeweller: “Our Wallace Bishop stores remained open during Covid-19 by implementing strict health and safety procedures, while our Hardy Brothers boutiques were temporarily closed in response to Covid-19 but have now resumed trading.”

Bishop confirmed that the current store count of 38 Wallace Bishop and five Hardy Brothers stores was the same as in the pre-Covid-19 period, adding, “There are no plans to close any stores in the foreseeable future. We continue to review our store footprint, which is ‘business as usual’ for the Wallace Bishop Group.

“Any store closures over the past 12 months were due to ‘end of lease’.”

While Wallace Bishop’s store count reduced by 33%, South Australia-based Shiels Jewellers managed to expand over the past decade with a major move into Queensland, where it opened seven stores.

In 2010 Shiels, owned by Transworld Enterprises, was the seventh-largest retail chain and 10 years later it has expanded from 31 stores to 36.

Interestingly, it has reduced its West Australian store count by five (17 to 12), while South Australia, where the company is based, increased by one (14 to 15).

Transworld’s second ‘brand’, Grahams Jewellers, closed two stores, down from eight in 2010 to six in 2020. However, according to Toby Bensimon, managing director of Transworld Enterprises, one more Grahams store is scheduled to close because “it’s not the right location”.

Rise and fall – and rise

Even more intriguing are the fortunes of Bevilles Jewellers. Once a bastion of Melbourne fine jewellery retailing, it was founded in 1934 by Leo and Rae Beville and has been in the hands of three generations of their family since, with granddaughter Michelle now CEO.

It first expanded outside of Victoria in 2003 when it opened its first NSW store at Parramatta. Today its store count stands at 24, compared with 29 in 2010.

While that figure indicates a loss of only five stores, the story is more complex – one that is both negative and positive.

While the recent history of Bevilles is tumultuous, its current position perhaps indicates the resilience of its management… [After] entering administration, the business was subsequently rebuilt, bringing its store count back to 24.

Not only does Bevilles operate fewer stores today than it did in 2010, over the ensuing years two stores were closed and, in April 2014, the chain entered voluntary administration.

As a result, Bevilles’ store count was forcibly reduced; 11 stores closed, bringing to 16 the number of stores across Victoria, NSW and South Australia.

However, the business was subsequently restructured and four months later a new store was opened at Melbourne’s Westfield Fountain Gate.

Then, in December 2015, the chain opened a new Melbourne CBD store, having exited Bourke Street Mall in 2011 when it was “outbid” by Swarosvki for the ‘flagship’ location where it had been mall positioned for more than a decade.

At the time, Michelle Beville said, “The lease was up and we put in a bid to renew, however the landlord decided to go out to market after international interest [from other retailers].

“International players have come to town and they have the ability to pay fabulous rent. The right rent moving forward [for smaller companies] is difficult, due to these international companies.”

In October 2017, Indian jewellery company Tara Jewels acquired a 49% stake in Bevilles, four years after forming a “strategic alliance” with the Australian jewellery retailer.

While the recent history of Bevilles is tumultuous, its current position perhaps indicates the resilience of its management; after ‘losing’ the high-profile Bourke Street Mall store and entering administration, the business was subsequently rebuilt, bringing its store count back to 24 – close to its peak of 29 in 2010.

By anyone’s reckoning, that’s no mean feat.

Another Victorian-based chain has also proved quite resilient over the past 10 years. Salera’s began 2010 with 21 stores – 15 in Victoria and six in Queensland – increasing to 23 the following year.

Alfredo Salera founded the business in 1953; by June 2020, its store count was 20 – an enviable and sustained record for a family-owned and operated mid-sized chain.

Hoskings Jewellers has also proved relatively robust. It made Jeweller’s list in 2010 with 17 stores, and today the Victorian-based jeweller still operates 16 outlets.

The company also owns the Goldsmith brand, which has been less fortunate; seven stores were closed in the past 10 years, with its numbers falling from nine to two.

With that said, three Goldsmith stores were converted to Pandora ‘Concept stores’; Hoskings now operates six Pandora stores in total (see Pandora).

The 2010 SOIR also detailed that Hoskings owned and operated four other jewellery stores: three under the Sterns brand and one Diamond House. These stores no longer exist.

Once again, taking into account the demise of many high profile and long-standing retail businesses across the apparel and fashion accessory categories, the resilience of fine jewellers is impressive.

Other well-known names that have stood the test of time include NSW’s Gregory Jewellers and Regency Jewellers. In 2010 Gregory Jewellers was listed as a small-sized chain with 16 stores and today it has 15.

While one Gregory store was technically closed, it was converted to a Gucci store operated by Gregorys.

Another small chain, Regency Jewellers, which was founded in 1968, has also fared well. It operated six stores throughout regional NSW in 2010 and it still operates the same number today.

The same cannot be said for the Queensland based Anthonys Fine Jewellers. It was listed with eight stores in the 2010 SOIR, however today it has been reduced to five across Brisbane. Owned by Queensland Wholesalers, the company also operated three Kings Jewellers stores in 2010 – all of which have ceased trading.

While Anthonys, with five stores, continues to be defined as a ‘chain’, the same cannot be said for Brisbane-based Pascoe Jewellers or Melbourne-based Dio Oro Jewellers.

Both have suffered over the past 10 years, with Pascoe having closed six stores (from nine to three) and Dio Oro reducing its store count from seven to one; therefore, both businesses have been removed from Jeweller’s ‘chain’ store list, along with Goldsmith, as mentioned previously.

While the wider Australian non-essential (discretionary spend) retail industry has suffered greatly in the past decade, it’s fair to say that many industry experts had predicted bleaker times for fine jewellery chains.

In the past decade only two names disappeared altogether and, although there has been a net loss of 118 stores, from the original 978, 63 closures were from Zamels alone.

Reviewing the past 10–15 years – the first of Jeweller’s analysis of jewellery chains was published in 2003 – many jewellers lamented the rise of, and competition from, fashion jewellery.

It was viewed as ‘cheap product’, however, this category has been impacted most by changes in the retail sector.

To that end, fine jewellery retailers have demonstrated an adaptability and buoyancy over the past decade that was not only unexpected, but should be celebrated given the current times.

Editor’s note: It should be recognised that even though some jewellery websites remain “live”, this does not mean the business or its bricks-and-mortar stores still operate.

BACKGROUND: STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT EXPLAINED

The first detailed analysis of the Australian jewellery industry was published in 2003.

It examined, and measured, the number of jewellery stores in the major shopping centres in each state and, interestingly, found that jewellers accounted for a ‘standard’ 5% of all specialty stores in major shopping centres.

The research also surveyed the number of jewellery chains and compared their store count by state with state population data.

In the following years, Jeweller conducted ad hoc research and in 2007 we published a more comprehensive analysis of chain stores.

At the time, there were around 1,000 stores listed, however a need emerged to refine the research by better defining store types and product categories. This process culminated in the 2010 State of the Industry Report, published in December that year.

The 68-page 2010 report offered a definition of – and differentiation between – independent jewellery businesses, fashion and fine jewellery stores, chain stores, brand-only and flagship stores, and finally jewellery kiosks.

Unsurprisingly, the jewellery industry has continued to evolve to the extent that, in some ways, it’s a little like going ‘back to the future’; the industry appears to be evolving full circle, back to its roots.

That is, independent jewellers are increasingly focusing on high-value items – often custom-made jewellery for specific clients – along with repairs and remodels.

In part, it’s a crucial move to differentiate from easily purchased, low-value/low-priced items sold on the internet.

At the same time, a notable change from previous reports is manufacturers altering their distribution models, becoming de facto retail operations that compete with independent jewellers.

What began as high-profile watch and jewellery brands establishing ‘Flagship’ stores – purported to assist independent stockists – has, in some cases, morphed into full-on competition.

As the industry changes in the coming years, there may be a need to re-evaluate the definitions used in future State of the Industry Reports.

Jeweller endeavours to maintain definitions where they are appropriate and relevant to the current trading environment, and to enable simple comparison with data in previous reports.

ZOOMING OUT: A HISTORY LESSON – PROUDS, ANGUS & COOTE AND GOLDMARK

While the New Zealand-based James Pascoe Ltd (JPL) represents the largest retail footprint across Australia – controlling Prouds, Angus & Coote and Goldmark chains – that wasn’t always the case.

As previously noted, the 2010 State of the Industry Report (SOIR) listed JPL with a combined total of 469 stores across its three chains, falling to 459 this year.

The accompanying chart shows the growth of the three chains since 2003, but it should be recognised that JPL acquired Angus & Coote (A&C) and Goldmark in 2007 in a $76 million deal. The acquisition included three other jewellery chains which were part of A&C and which no longer operate.

A&C was established in 1895 and was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) in 1952. At the time of the JPL takeover – which required approval from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) – A&C operated the Edments, Dunklings and Amies chain, as well as Goldmark.

At the time of Jeweller’s first chain store research and analysis in 2003, A&C operated 254 stores (Goldmark 114, Amies 34, Dunklings 26, Edments 25, A&C 55) and according to research firm IBISworld, the company had 12% of the jewellery and watch store business.

The deal was controversial not only because it required ACCC approval, but also because it was a ‘reverse takeover’ – named for when a smaller company attempts to acquire a larger company.

JPL announced the takeover move in January 2007 when it had around 174 Prouds stores in Australia and when the ASX-listed A&C accounted for around 246 stores.

In addition, Prouds was only the third-largest group at the time of the reverse takeover; Kleins, a fashion jewellery franchise, was the second-largest chain/group, with 182 stores.

In another interesting twist, reminiscent of recent history, in May 2008 Kleins was placed into receivership after collapsing with $20 million in debt. Two months later the company was liquidated after administrator James Stewart, of Ferrier Hodgson, said he was being forced to close the business.

“Despite 46 expressions of interest and eight indicative offers being received, once parties proceeded to due diligence it was clear that no-one was confident about returning the business to profitability, considering the risks and financial commitment required,” Stewart said.

In November 2008 Prouds went on to re-brand Amies in Queensland, Dunklings in Victoria and Edments in South Australia and Western Australia as Angus & Coote stores, which helps explain the increase from 41 stores in 2007 to 133 in 2010, and finally 122 this year.

And in one final twist, of the 1,224 chain stores across Australia in 2020, 50% are owned and ‘controlled’ by the Kiwis: James Pascoe Ltd and Michael Hill International.

ZOOMING IN: PANDORA – PAST THE PEAK?

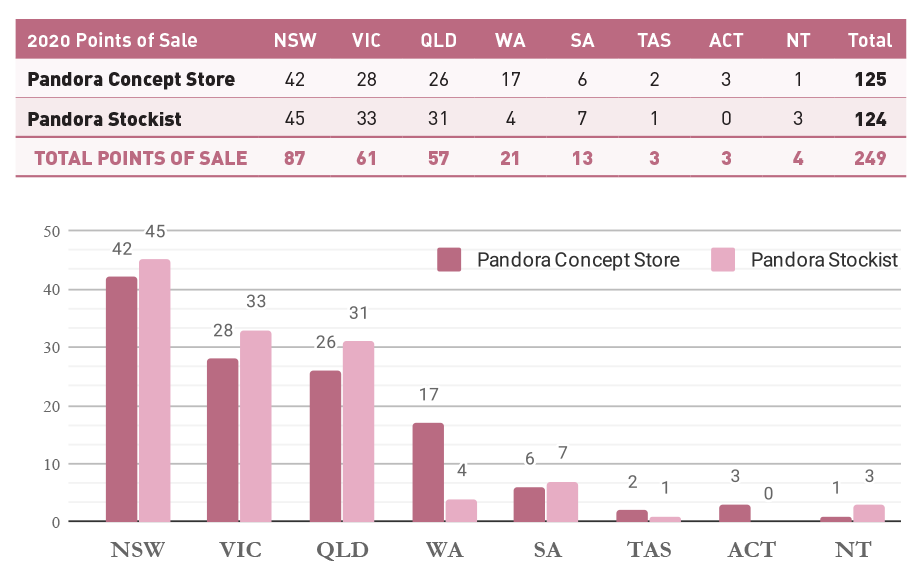

While the accompanying fine jewellery chain store analysis does not include Pandora, its store count has been included in the 2020 Chain Store table.

The company and brand was defined as a ‘brand-only’ chain in the 2010 State of the Industry Report (SOIR) – rather than a fine jewellery chain.

The distinction is important because Pandora was, and remains, both a supplier to the wider jewellery market and a prominent retailer of its own brand.

For this reason, the 2010 SOIR listed Pandora as a ‘brand-only’ operator, which was defined as “one, or more, fine or fashion jewellery stores that sells and markets its own brand of jewellery and/or watches.

It is usually a vertical-market operation, does not utilise local suppliers, and stores are often owned and operated by the proprietor of the brand or under license via franchise agreements.”

Since 2010 the Pandora ‘Concept’ (brand-only) stores – many of which are operated by franchisees – have increased from 41 to 125. However, a number of the stores have closed in recent times.

Pandora Australia refused to divulge the figure, but it is rumoured to be approximately five.

Traditional jewellers once frowned upon Pandora jewellery as a cheap fashion product; however the line between fashion and fine jewellery is often subjective and it was blurred when Pandora’s designs began using gold and diamonds.

Further, the dismissive ‘fashion’ tag flew in the face of Pandora’s successful distribution model, and which best demonstrates the evolution of the brand and the industry.

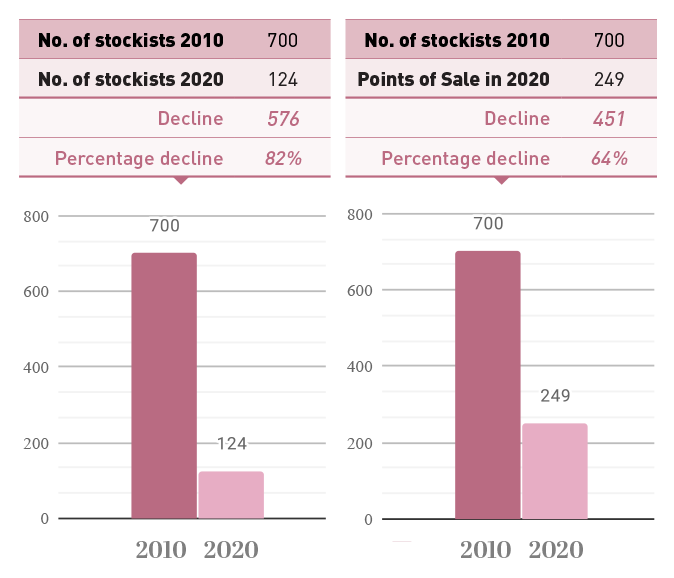

That is, by around 2010 Pandora was sold by more than 700 independent jewellery stockists.

Following a six-year run of meteoric growth, the company began closing accounts in Australia and New Zealand; during 2011 alone, more than 100 stockists had their accounts closed as Pandora entered a “new business phase in Australasia”.

The news struck the industry hard, but more was to come.

In 2012, Pandora Australia announced a further 100 stockists would be closed while at the same time pushing its own franchise model.

The table below shows that from a peak of more than 700 Australian independent stockists, the brand is supported by only 124 stores today. In other words, Pandora maintains only 18% of its independent consumer distribution points as it did at its peak.

Adding the Pandora franchise stores, that figure reaches around 35%.

In fairness, much of the decline has been at the company’s choice; however, the way it has managed itself over recent years caused many jewellers to quit the brand – with some making the decision for Pandora.

Reasons for no longer stocking Pandora have included what many saw as excessive and unfair trading terms and conditions, along with being treated as ‘second-class citizens’ compared to the franchise operators.

For example, the increased number of forced deliveries per year gave retailers little choice in their own stock levels.

Combined with minimum quantities on each item (i.e. pack sizes of three-of-kind), independent stockists were prevented from matching stock purchases with sales, resulting in ever-increasing stock levels.

The over-stocking problem increased to such an extent that, in August 2019, the company took the extraordinary step of buying back jewellery from stockists for smelting.

However, even the buy-back program was saddled with strict conditions, including that retailers would be charged a handling fee.

The retailers’ decision to stop stocking Pandora may have been well-founded, given that over the past three to four years, Pandora sales have been declining – to the extent that in 2019, the company announced an international ‘re-launch’ of the brand.

Less than two years after announcing that it would focus on its company-owned and franchise stores, thereby closing thousands more wholesale accounts from its independent jewellery retailers, Pandora Jewelry CEO Alexander Lacik declared in February this year that that may have been a poor decision.

Lacik, who joined Pandora in April 2019 from outside the jewellery industry, believes the company might have lost “a lot of new customers” and may need to refocus on distribution to independent jewellery stores – the very businesses that it once discarded.

HILLS & VALLEYS: KEY MOMENTS FOR MICHAEL HILL

It’s been a topsy-turvy decade for Michael Hill International.

Following the opening of his first store in 1979 in the New Zealand town of Whangarei, jeweller Michael Hill became well known for unique designs and utilised high-impact advertising to elevate the business to national prominence.

The company grew steadily, and by 1987 it had 10 stores and was listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX). At the same time, the company expanded into Australia, opening four stores in Brisbane over four weeks.

In 2002, the company opened five stores in Canada and six years later made inroads into the US market by acquiring and re-branding 17 stores from Whitehall Jewelers.

In January 2011, and the age of 72, founder Michael Hill was granted a knighthood in New Zealand’s New Year Honours List.

After a long and illustrious career, Sir Michael retired as his namesake company’s chairman in November 2015 and the following year Michael Hill International (MHI) was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX).

At the time, 60% of its stores were in Australia and more than 80% of MHI’s revenue and profits were generated outside of New Zealand.

The company began trading on 7 July 2016 at $1.15 per share. At the time of publication its share price was $AU0.32 on the ASX and $NZ0.34 on the NZX.

The company’s 2019 Annual Report recorded a total of 306 stores; 168 stores in Australia (dropping to 156 by July 2020), 52 in New Zealand and 86 in Canada. It reported revenue of $569 million and post-tax profit of $16.5 million. In October 2016 the Hill family trust, Hoglett Hamlet, sold 10% of its stake – 16 million shares – in MHI for $25.6 million. However, it remains the company’s largest shareholder, owning 38% of the company.

Report republished with permission from Jeweller, Australia’s #1 jewellery industry magazine. Please view the original story with comprehensive notations and interactive charts here.