The selling of simulants and synthetics mixed with parcels of natural stones is an old form of deception. It usually happens close to mines, where inexperienced buyers assume the gemstones come directly from the source—and where advanced testing is likely not available prior to the purchase.

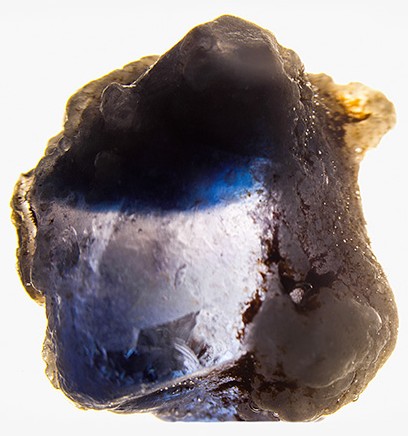

The Carlsbad laboratory recently received a group of four blue rough stones (figure 1) submitted as natural sapphire for identification and origin reports. The largest weighed 48.63 ct and measured approximately 22.88 × 19.67 × 15.19 mm. The material was partially fashioned, with evidence of polish lines on the surfaces. Careful microscopic examination revealed multiple gas bubbles, distinct flow marks associated with blue coloration, and conchoidal fractures. Weak snake pattern bands were observed under the polariscope. The hydrostatic specific gravity was 2.48. These observations suggested a glass imitation, which was confirmed by comparing the infrared spectrum with that of manmade glass.

The next two were more convincing imitations of natural sapphire. They weighed 9.17 and 6.21 ct and measured approximately 16.00 ×10.06 × 8.30 mm and 10.31 × 9.38 × 8.71 mm, respectively. Resin that coated the surface (figure 2) resembled matrix composed of natural minerals commonly seen on natural corundum rough. The resin started to melt with the touch of a hot pointer. Brownish materials trapped in cavities resembled iron oxide stains one would expect to see in natural rough. Though difficult to see inside of the stones due to their rough surfaces, a few gas bubbles were observed through a small transparent area. Raman spectroscopy matched corundum, and immersion in water (figure 3) revealed curved blue banding. Laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) detected no gallium and revealed trace elements of impurities consistent with synthetic corundum. Hydrostatic specific gravity values were 3.76 and 3.59, respectively. Both values were below the SG of corundum (3.9–4.05), a result of the lower SG of the resin on the surface. Both were reported as laboratory-grown sapphire with a comment stating, “Imitation matrix and resin is present on the surface.”

The last piece of rough was a blue stone weighing 8.46 ct and measuring 13.85 × 9.89 × 7.60 mm. The frosted natural surface made it difficult to see inside the stone, but some natural-looking fingerprints and strong, straight inky blue banding were observed. The Raman spectrum matched with corundum, and a hydrostatic SG of 3.96 confirmed it. The stone was immersed in methylene iodide to confirm the zoning was straight and not curved. Medium chalky blue fluorescence to short-wave UV and a strong 3309 cm–1 series in its Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum proved that heat treatment had been applied to the stone. LA-ICP-MS revealed natural chemistry, including about 200 ppma iron and other trace elements such as gallium (~25 ppma), vanadium (~3.5 ppma), magnesium (~35 ppma), chromium (~1.5 ppma), and titanium (~80 ppma). Based on appearance, color zoning, and chemistry, this stone was reported as natural sapphire, heat treated, with Madagascar as the country of origin.

This was an interesting study of how synthetics and simulants can be mixed with their natural counterparts to misrepresent a parcel. However, careful examination and standard gemological testing are usually enough to identify them correctly.

This article is republished with permission from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA).