For those who hoped for a stable 2011 after the tumultuous previous two years, the first eight months of 2011 did not provide any respite. In the January to July period this year, diamond prices moved up by an unprecedented 40%. In August, imbalances and global uncertainties caught up with the industry. Are we in for a repeat of 2008? Diamond industry expert Pranay Na rvekar does not think so, unless there is another global crisis.

The industry began 2011 following a fairly quiet fourth quarter in 2010, where demand and prices had shown signs of stabilising. However the quarter also saw the US introduce its second quantitative easing (QE2) package. This package pumped liquidity into the US economy, which later was passed on to countries exporting to the US and ultimately into commodities. Some of these monies also found their way into diamonds.

As QE2 started having an effect on the US economy, retail sales increased and retailers had to upgrade their forecasts to keep in line with actual off-take. This led the industry to enjoy the positive impact of the bull-whip effect in the first half of 2011. Retailers started purchasing polished, both for replenishing their shelves, while also increasing their target stocking levels to keep pace with their rising sales.

Another impact of QE2 was that the excess dollar liquidity led to its weakening in relation to other global currencies.

Diamonds are essentially priced and dealt predominantly in US dollars. Hence this resulted in diamonds becoming relatively cheaper, thereby spurring demand.

Galloping demand

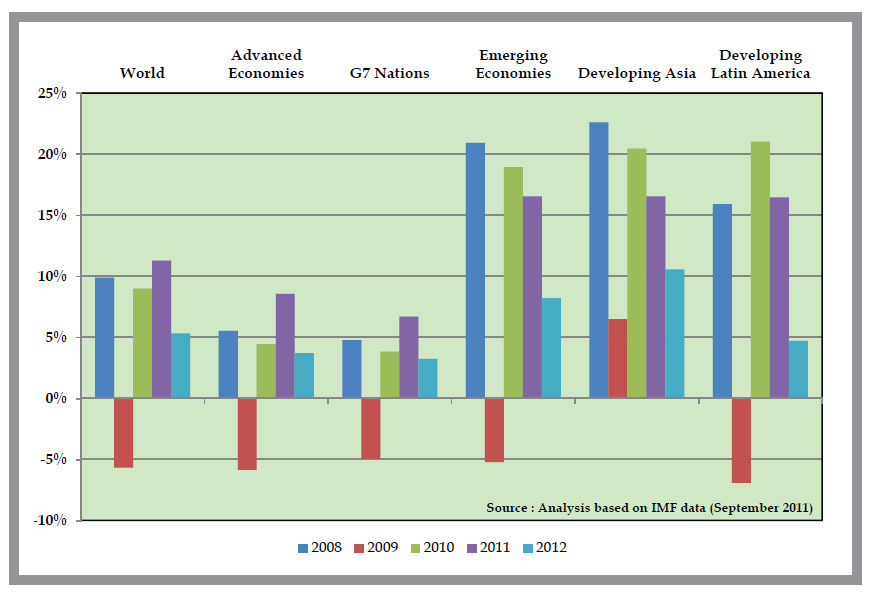

Inflationary demand in emerging countries like India and China also spurred diamond demand, which depends more on the nominal (i.e. real + inflation) growth in GDP, rather than only the real growth, which typically gets reported. As the dollar weakened, it further showed up as additional demand from the emerging countries.

The Chinese, in particular, have also developed a taste for acquiring branded goods, very much like the Japanese over three decades ago. Well-established luxury brands, especially watches, saw a huge increase in demand. Watch manufacturers upped their production schedules and demanded more polished in the top makes. This greatly increased the spreads between polished of the best makes and the other ordinary makes, which was a phenomenon unique to 2011.

All these factors added up to create a demand pull for both polished and rough, setting the stage for the explosive industry growth.

Supply constraints

Internal industry dynamics also played their part. The predominant driver was lower carats which were sold by the producers. There were numerous factors for this, most of them being specific to each mine. Most producers had stabilised production after the crisis and had had a good 2010. Some mines had decided to keep production at existing levels, and did not want to increase output to levels achieved in 2007. Some mines started maintenance and upgrading activities which had been delayed during 2009. Others decided to mine lower yielding areas, which had also been avoided during the crisis, while some mines genuinely had lower production. In times of higher prices, the impact of lower production quantities is less severe on the cash flow of the miners. The cumulative effect of all this put together was 5-10% reduction in carats, just at the time when demand increased.

The polishing side of the industry was also facing its own issues. The industry, especially in India, had not been able to get back the polishers who had been lost during the slowdown due to the global economic crisis. To maximise the production value, units started moving up in size and quality, hoping to achieve greater turnovers. This meant that the shortage of smaller-sized polished was also felt, along with rising rough prices.

Prices affecting behaviour

The increase in demand coupled with the decrease in carat supply resulted in a demand supply mismatch. This pushed prices of both polished and rough diamonds higher. As the price increases started to take hold, rough and polished prices in the smalls category led the charge.

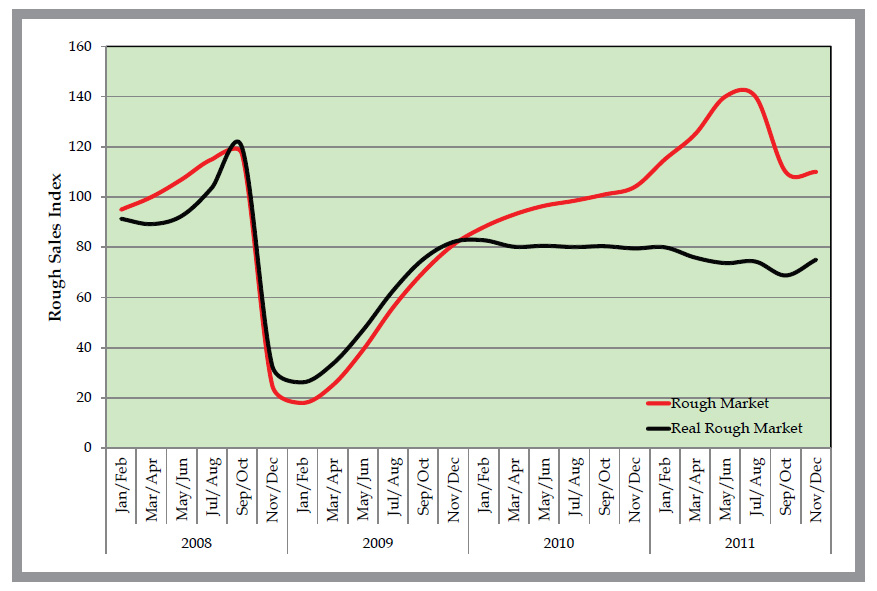

Comparing the size of the nominal and real rough market shows the discrepancy between the two. In 2011 the real rough market (i.e. at constant prices) actually reduced, or in other words supplies were lower, compared to the nominal market. The difference between the two shows the impact of prices.

Price increases also affected the behaviour of retailers, who started buying and stockpiling polished for future orders, as they were not confident of the price at which they could source the polished. Purchase orders were advanced, which put an even greater strain on the constrained supplies. The flip side of the coin is that the orders will reduce as we get to the end of the year, something not seen in past years.

Manufacturers started factoring in the price increase while buying the rough, i.e. rough would only be profitable if the polished prices increased between the time the rough was purchased and the resultant polished received or sold. Gradually, it reached a stage where only a double-digit increase in polished prices over 3-4 months could justify the price of the rough.

Rough tenders, which have increased over the last three years, provided a fairly transparent mechanism to judge price movements, further fuelling speculation. The price increases in the tenders helped push the market into a flurry, where rough had to be sourced at any cost.

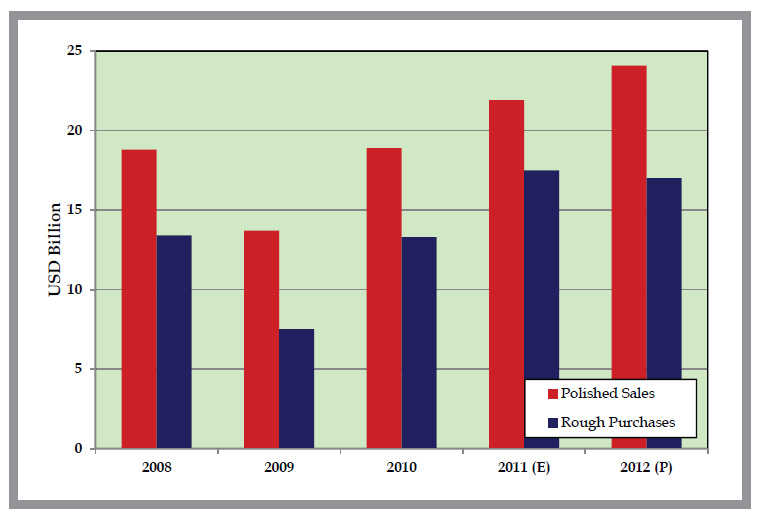

Another reflection of the market buoyancy was the trading within the industry. As the prices moved up, the profits which were made got reinvested into stocks, more so in rough than in polished. The desire to increase stocks energised trading within the industry which pushed up the turnovers. After April in the new financial year, Indian companies were able to raise their borrowing limits from diamond financing banks to keep up with the increase in sales. Without noticing it, industry stocks and receivables reached record levels as did bank liabilities.

These factors ensured that rough prices outshot polished prices as the industry lost sight of the fundamentals.

The polishing side of the industry was also facing its own issues. The industry, especially in India, had not been able to get back the polishers who had been lost during the slowdown due to the global economic crisis.

Turning point

As in all bubbles, prices got to a point where even the best manufacturer could not justify the rough prices being paid. Some pure polishers also started to speculate in rough, buying the rough with a view to holding it for a couple of months before reselling the same. Prices, it seemed, were driven simply on the hope that prices would rise in the future rather than based on any fundamental principle. It was estimated that the industry had stocked up about $2 billion-worth of goods, more than that which was required.

It was already clear by April that demand projections indicated that prices would have to correct. The industry prices had risen by more than 25% after that point itself. Further increases till August meant that both the duration of the correction was reduced, while the quantum of correction increased. Expectations of the drop became more severe.

By early August, global uncertainties seemed to catch up with the industry. Bank borrowing, especially in India, which had increased, started to hit limits. Indian banks also found it increasingly difficult to raise dollars. Finance, even when available, was in Indian rupees which made it much costlier for the industry to borrow.

Global sentiments also changed, with the uncertainty over Greece. This impacted the markets, eroding the feel-good wealth factor as global sentiments changed.

Speculators suddenly realised that they could exit only with a loss. Tender prices showed nearly a 20% drop on a month to month basis. The natural reaction of traders was to cut down their purchases. Payments were also delayed. This reduced the transaction volumes in the industry as internal trading reduced to the bare minimum, constraining borrowing even more. This impact of volume reduction on bank lines will only be seen after 3-6 months.

The industry optimism for the first seven months of 2011 was replaced by a grim view on whether it was a repeat of 2008 which was unfolding.

Deja vu 2008?

The current situation is in many ways similar to that faced in 2008. During both the years, there was a dramatic rise in prices over the first half of the year. These started to moderate by early August. In 2008 too, the industry would have gone through a similar, but less severe correction even if the global crisis had not been precipitated—the reason being, diamond prices had risen by about 15-20% in 2008 instead of the 40% in 2011.

What triggered the next set of events in 2008 is the Lehmann Brothers crisis, which suddenly froze the global markets and sucked out liquidity. This brought banks to a near collapse and plunged the world into a recession. The resultant impact on the demand for jewellery worked itself through the diamond supply chain over the next 9-12 months affecting retailers, diamantaires and the rough producers.

A similar global event cannot be ruled out and if it were to happen, it would further affect rough and polished diamond demand in a manner similar to the 2008 crisis. This time round, though, governments are watching carefully and are better prepared to support the global economy in a crisis, and hope for an orderly unwinding of the crisis.

Make no mistake, even without a global recession, the next 18 months will be a difficult period for the industry. Another global shock will only make it worse.

crystal-ball gazing

Over the next 4-6 months, the industry will need to work through the challenges it faces mainly stemming from a price adjustment, liquidity constraint and excess stocks. Given the current state of the industry, the response of the major producers will determine how quickly the industry will get out of the crisis. If they insist on pushing carats into the market, prices will fall steeply.

The Diamond Trading Company (DTC) has already announced a smaller September sight. Similar actions by Alrosa will go a long way in allowing the industry the time it needs to work through its problems. Both these companies did show their leadership during the 2008 crisis, and the industry possibly needs similar actions again.

Rough prices have dropped by about 30-35% from the heady peaks of July. At these levels manufacturing again becomes viable, which should see a re-emergence of demand. Polished prices have managed to hold ground better and corrected by 5-10%. Calculations indicate that prices will only see minor adjustments of 5-10% from here, unless there is another global event triggering a recession.

Looking beyond the current stumble, challenges would continue into 2012. Part of this concern is justified given that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already reduced their growth forecasts. Even before 2011 started, calculations showed that 2011 rough purchases would be buoyed by a restocking demand, which will be muted in 2012. Even with a reasonably optimistic retail growth forecast of 7.2% for 2012, it looks likely that industry rough purchases will decline slightly. If additional mine supplies, which are expected to be available, reach the market, there could be a greater price correction in the rough. Polished demand is expected to increase, as the industry destocks. While current secondary market rough prices should be able to sustain full volumes for 2012, the question will remain whether the industry can avoid overpaying for rough again.

Make no mistake, even without a global recession, the next 18 months will be a difficult period for the industry. Another global shock will only make it worse.