The global diamond industry finds itself in a quagmire of its own doing. India’s top diamond industry analyst PRANAY NARVEKAR examines the health of the industry and offers remedial measures to check practices that have led the industry to the vicious cycle it finds itself in today.

In Indian mythology, the “chakravyuh” refers to a military formation which is nearly impossible to beat. However at a more figurative level, the “chakravyuh” refers to a situation which is easy to enter, but impossible to escape, illustrated by the sad story of Abhimanyu, the son of Arjun, in the Mahabharata. The events of the last few years have transformed the diamond industry, through willing and unwilling actions of rough producers, diamantaires and banks into a chakravyuh, a situation which no one wants to be in. That is the real drama, where we either change or perish. Moreover, we need to explore whether change can be brought through collective action, or whether it is an “everybody fends for himself ” situation. Ideally, we find a combination of these options at our disposal.

The breakdown of the trust was a gradual process. It was triggered during the 2007 period, when global rough production started to fall.”

The build-up

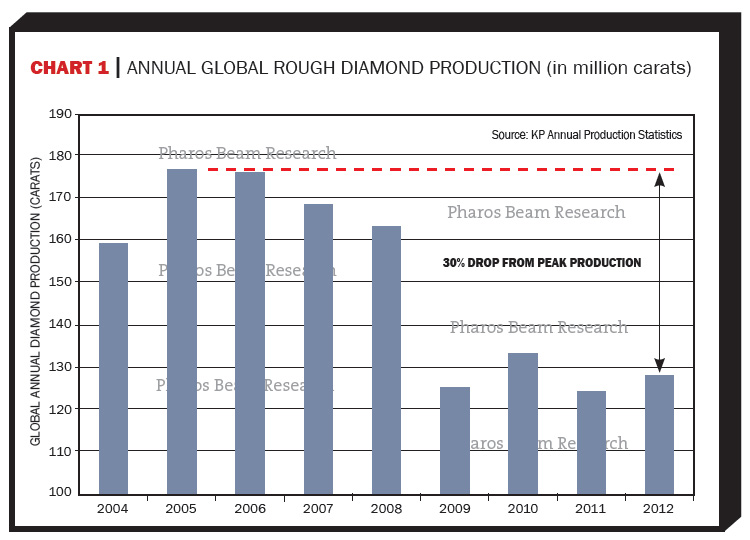

The breakdown of the trust was a gradual process. It was triggered during the 2007 period, when global rough production started to fall. The midstream industry had built up capacities to manage greater volumes of rough. The drop in production triggered a huge demand for rough, as companies looked to keep their factories running at full capacities (see Chart 1).

While the crash of 2008 forced the industry to reduce its capacity (and workers), the producers with long-term contracts felt betrayed, as diamantaires refused to purchase the contracted rough. The genesis of that action was the result of what had happened in the market over the previous decade.

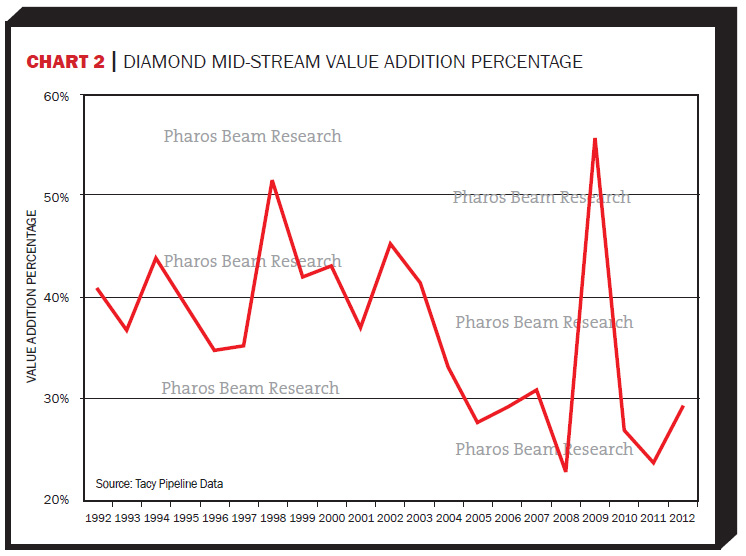

The diamantaires had always played a valuable part of the diamond pipeline. During the 70s and the 80s, the midstream typically added nearly 2/3rds of the value of the final polished sold to consumers. By the 1990s this had settled to about 40%, as technology coupled with production capacities in India ramped up. The value addition showed the most noticeable drop in the 2001-2007 period as diamond polishing industrialised, and India emerged as the premier diamond polishing hub, even while production was being increased. To be fair, there were technological advancements as Surat became the main global hub for diamond polishing.

Chart 2 shows the midstream value addition as compared to the Retail PWP of the pipeline. The Value Addition is the difference between the dollar values of the rough sales and the Retail PWP taken from the Tacy Pipeline. Over the same 20- year period, in gross dollar terms, the value addition in the industry has remained flat. During the same period, the dollar has devalued by more than 45% in real terms due to inflation, which increases the cost of doing business. Simply put, in a like-to like comparison, after 20 years, the industry earns only 55%, in adjusted dollars, of what it did 20 years ago.

This was echoed recently by De Beers’ Varda Shine, who recently mentioned that the industry “will need to change”. What this probably meant was that, apart from supply-demand driven fluctuations, the margins historically allowed in the rough category and the added value (i.e. margins) which producers “left” for their clients will not be seen again, at least willingly.

The dropping value addition also fundamentally affected the way the business was financed. As midstream businesses felt the pressure of reducing margins, a natural reaction was to increase the leverage in the business, to ensure that their returns on equity were healthy. Banks were awash with funds after the liquidity injection following the dot-com crash and were more than happy to lend to an industry which had low historical bankruptcies.

This led to a paradoxical situation, where the industry was ramping up capacity to keep up with the increased rough production, while also seeing their margins reduce. The secret sauce was finance, which enabled the industry to keep purchasing rough, even while its value addition was reducing. A part of this shift was due to the relocation of manufacturing centres to India, China and other South-east Asian countries to meet cost pressures. This was happening at a time when the Indian rupee and other currencies were nearly flat, indicating that it was more to do with simple cost arbitrage. Manufacturing in traditional centres like Belgium and Israel withered, however stocks and risks remained with these centres, till things came to a head during the 2008 crisis.

As midstream businesses felt the pressure of reducing margins, a natural reaction was to increase the leverage in the business, to ensure that their returns on equity were healthy.”

Diamantaires had realised that, like gold, the profits from price increases in rough and polished, could be much higher than the regular manufacturing profits. Hence these new (and cheap) funds were used, in lieu of equity, to primarily increase the inventory, with some going into funding memo programmes. This increased not only the leverage, but also the riskiness of the balance sheets, but that fact was ignored. This leverage was more visible on the balance sheets of companies in Antwerp and Israel, the locations having relatively higher costs and much easier access to finance.

The other factor was the introduction of the Supplier of Choice. It pushed the midstream to invest into more downstream activities like jewellery, branding and retail, something in which they had no expertise and ultimately most people ended up losing money. While its original intention was to improve the industry bottom-line, what ended up happening is that diamantaires focussed on top-line growth at any cost to obtain supply privileges. To push sales, companies needed to hold more inventory, which in turn ensured that rough prices remained high. This was a double whammy to the profitability and ultimately the equity in the industry.

Risks shift to India

The 2008 crisis pushed the industry to the brink. Much has been written about how the crisis panned out, however, sensible reactions by all concerned and steps taken by nations globally ensured a relatively fast recovery. Industry participants also took their fair share of responsibility, including producers, who reduced rough supplies and prices, and banks, which supported most of their clients.

However, the major shift caused by the crisis was India becoming a more prominent centre. As rough production dropped, India started producing larger sizes and better quality goods, as it continued to be a low-cost centre. Supporting government policies meant that it also became a trading hub for polished. In relative terms, the impact of the 2008 crisis was fairly short-lived for Indian companies.

As mentioned, other global centres were more leveraged and carried greater stock and receivable risks. Hence the banks at these locations were more careful about how they lent monies. Credit was gradually tightened in both Belgium and Israel, and companies were forced to reduce their exposures.

At the same time, Indian banks kept providing liquidity, initially driven by government directions to assist the industry and later as the industry became convenient for them to increase their lending with minimal efforts. This ensured that during the 2008-2011 period, the industry stocks and receivables, i.e. risks, grew more in India, than at other locations.

The impact on the thinking of producers was more severe. During the early crisis, the refusal of long-term clients to buy their sights which were then priced higher than market prices was considered almost a betrayal and hurt their core belief in how the long-term contracts should function. This thinking did not consider the gradual erosion in midstream equity or their mistimed price increases. It sharpened their resolve to be more reactive in price increases.

The first half of 2011 proved to be the golden period for the industry, when prices moved up rapidly, driven by surging global demand and stocking requirements. During this period, the rough producers reacted much faster to raise prices. This meant that while the industry made healthy profits, these were essentially held in stocks, with most of the cash flowing to the rough producers. The book profits, from stocks, meant that companies were able to borrow more.

When prices slumped in the latter part of 2011, the primary rough producers maintained the price of rough above sustainable prices. Producers realised it is convenient to sell at the higher market rough price or sustainable rough prices based on market conditions. It was not considered that it was the midstream equity created in early 2011, leveraging and the diamantaire’s fear of reduced rough supplies which enabled them to sell at higher prices till mid-2012.

This was visible in the value addition, which again slumped. However, this time around, it was not due to improving efficiency or shifting polishing to locations which offer even lower cost, but it came directly from the midstream profitability.

The first half of 2011 proved to be the golden period for the industry, when prices moved up rapidly, driven by surging global demand and stocking requirements.During this period, the rough producers reacted much faster to raise prices.”

Rupee Volatility: Does it really matter?

For Indian banks, the Rupee volatility has made it more difficult to judge the profitability and the financials of domestic companies. The recent Rupee volatility has been cited as a reason for rough being unaffordable to smaller manufacturers. However, that is not a plausible explanation.

Dollar prices do affect the availability of funds for the industry. A 10% weakening will reduce the value of funds held in Rupees, or even the borrowing capacity for the industry, which is also set in Rupees, i.e. companies will be able to buy 10% fewer carats. What will surely be affected would be the local demand for polished. Indian consumers have a finite wallet and jewellers also target price points. If Indian demand accounts for 8% of global demand, a 10% weakening in Rupee will reduce the global demand by 0.8%.

However, whether the rough is expensive or cheap depends on the prices which producers charge and the demand for that rough and polished. Polished prices also increase as the Rupee weakens, leading to more gains on the sales side. All that would be effectively pure profit for the companies holding the stock. Apart from this windfall gain, production costs might go down as labour is paid in Rupees, after factoring in the inflation in wages.

Hence, from an accounting perspective, a Rupee weakness is good for Indian companies, who get windfall gains. However on an operational basis, that is incorrect. IFRS also recommends that company accounts should be in the currency of primary exposure, which would be US dollars for the industry. While that is not currently allowed, at least in India, companies should take a replacement cost view. The newer rough comes in at a higher price, and there are no ongoing profits.

Breakdown of trust

As the midstream grapples with its own survival, it is questioning the intent of the producers. They believe that the producers are no longer concerned about the financial well-being of the midstream. It is ironic, because financial health is a mandatory criterion for a company to become a sightholder! Unfortunately there is no best practice principle for ensuring midstream profitability.

Producers realised it is convenient to sell at the higher market rough price or sustainable rough prices based on market conditions.”

The more serious and immediate concern is that the banks believe this too. Sightholders were assumed to be risk-free customers for banks, as they had confidence in the rough producers. That tenet has been shaken, with banks having conveyed to the producers that they might even think about not financing purchases from particular producers. Those however, still remain threats.

Global banks with specialised industry expertise have been seeing a far more distressing trend as leverage in the industry has been increasing. They have already been voicing their concerns since over a year. They have been paring down their lending and exiting certain accounts they are not comfortable with, even at the cost of write-offs.

Indian banks seemed less concerned about this, but that perception is changing. The reintroduction of import duties last year helped curb some of the malpractices in the diamond business, leading to a drop in diamond exports, but then the action shifted to gold and gold jewellery. The government’s enthusiasm for reducing imports of gold, as well as the recent issues with a few public companies have made Indian banks more circumspect in increasing lending.

During the Banking Conclave, bankers mentioned their apprehension and also showed the loopholes in the credit risk management processes followed. As a follow-up and in order to collate banking exposure to the industry, the GJEPC sent letters to about 25 banks. Sadly, in nearly two months, the response has been in the low single digits. This truly reflects the lip service given to risk management in the industry by banks in India.

Indian banks continue to be liberal. Few companies are reported to have completed their balance sheets in record time and submitted them for increasing borrowing limits, and have been granted large increases in their borrowing base. While a few stray individual cases may merit some enhancement, the overall industry scenario is certainly not healthy. In such an environment, where experienced bankers are sceptical about industry health, it is confounding that banks can still justify these large increases in limits for clients to their respective boards. I guess that might be a matter for future investigations.

All these only highlight the shift to short-term thinking in the business. The relationship between producers and diamantaires has shifted from trust-based to merely transactional. This shift is also visible between banks and their customers. That might not be necessarily a good thing for banks, because it might capture the ability, on books, to pay back the monies, but it does not capture the real capability and the intent to pay back, which can only be judged based on relationships.

Indian banks continue to be liberal. Few companies are reported to have completed their balance sheets in record time and submitted them for increasing borrowing limits, and have been granted large increases in their borrowing base.”

The path ahead

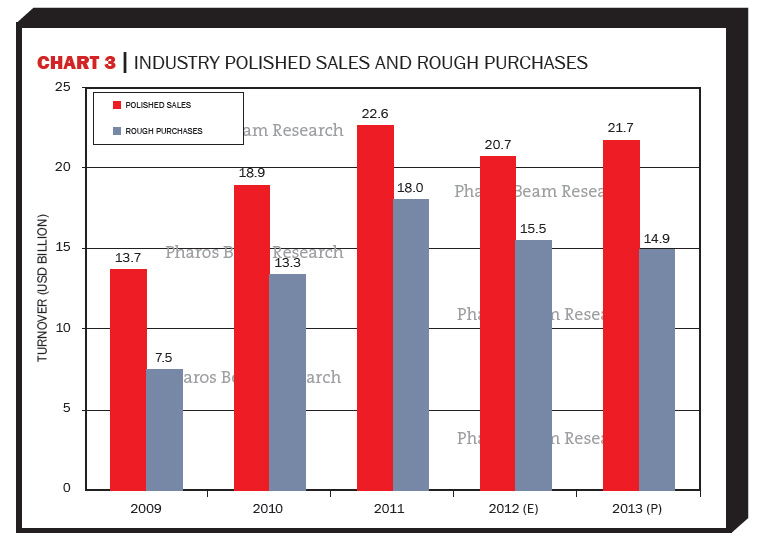

The price rises in 2011 triggered adjustments by retailers, where they reduced the Diamond Content of the jewellery to achieve price points. This affected demand over the 2012-2013 period. Global challenges also meant that consumer demand growth was soft. While polished demand in 2013 is expected to be higher than 2012, rough demand is expected to be lower (see Chart 3). The big question while forecasting demand remains the liquidity scenario and what will be actions taken by banks. The scenario assumes some reduction in bank credit, but stricter action could reduce rough demand even more.

At these levels, rough prices would also be expected to soften between 4-5% for the year. A longer term forecast indicates that rough prices would remain flat over the next 3-5 years in the absence of any external dislocations. This would also mean that companies would need to get their business profitability in order, and cannot necessarily depend on stock price increases to shore up their profitability. Given this scenario, does the industry have any way out of the chakravyuh?

Unfortunately, exiting the chakravyuh is more difficult, if at all possible. In a way it mirrors the global situation, where central bankers have pumped in money through various means, but the events in June show that exiting the easy money scenario will be painful. For starters, all stakeholders should realise certain facts about the industry.

- We are in a mature industry. While efficient companies can still grow, super-normal growth can come only at the price of margins

- The industry should not bank on stock price rise to shore up profitability from operations

- Leverage means higher risk. Industry, like the rest of the world, needs to de-leverage.

- Individual businesses (rough, polished, jewellery, retail etc.) should be profitable in their own right, and crosssubsidies help only in the short-term

- Business is not homogeneous. Dynamics and profitability of different types of business is different and demand-supply is getting increasingly fragmented

- Ultimately, if the product does not reach the consumer or if the consumer does not buy, everyone loses

Let’s consider two extreme scenarios:

A doomsday scenario involves the party continuing till the time there is a massive shakeout. Most of the smaller and higher leveraged companies will go out of business. Banks would face large write-offs and the domino effect of the bankruptcies would leave most companies in a very weak state. With little bank financing left, rough prices would drop drastically, forcing marginal mines into closure. Retailers will struggle to get necessary supplies for an extended period, forcing many of them to look at alternatives, including synthetics. Diamonds will lose their emotional hook with consumers. The remaining natural diamond industry would move back to dealing in better quality stones. The midstream would become oligopolistic, with few companies standing. However, the industry would be a fraction of its original size.

A utopian scenario would be quite the opposite. Rough producers would lower prices while banks will finance only 80% of rough purchases. There would be a shortterm drop in rough purchases, but it would recover in about 2-4 months. Bank limits would be maintained and reduced over a period of time, allowing the industry to de-leverage as equity is rebuilt through profitable operations. A few over-leveraged companies might fail, but the overall health of the industry improves. Industry focuses on business basics, ensuring a healthy profitability, without resorting to reducing polished prices to offset the drop in rough prices.

The reality would lie somewhere between these two scenarios. It would also mean that all concerned parties accept the realities of the business and align their mutual priorities. While one would hope for the utopian scenario to pan out, short-term pain may not be easy to digest. History, unfortunately, shows that our capability to accept voluntary pain is extremely limited.

Unfortunately, exiting the chakravyuh is more difficult, if at all possible. In a way it mirrors the global situation, where central bankers have pumped in money through various means, but the events in June show that exiting the easy money scenario will be painful.”